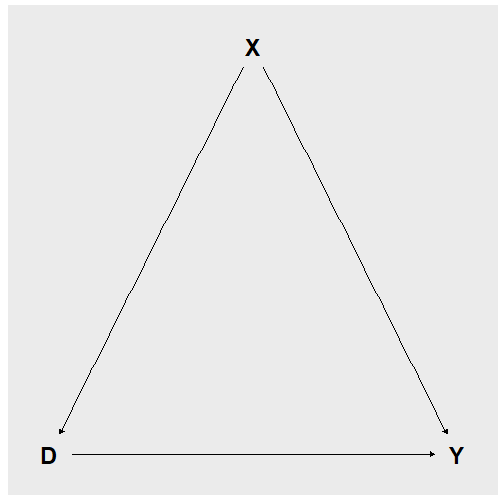

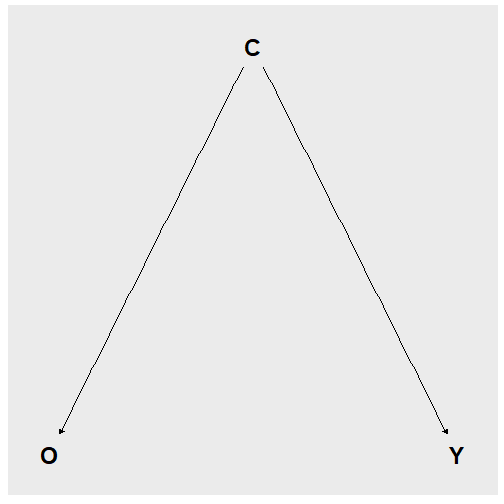

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # ML in Aid of Estimation: Part I ## Lasso and ATE ### Itamar Caspi ### May 5, 2019 (updated: 2019-05-06) --- # Replicating this presentation Use the [pacman](https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pacman/vignettes/Introduction_to_pacman.html) package to install and load packages: ```r if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman") pacman::p_load(tidyverse, tidymodels, hdm, ggdag, knitr, xaringan, RefManageR) ``` --- # Outline 1. [Causal Inference and Treatment Effects](#causal) 2. [Variable Selection Using the Lasso](#Lasso) 3. [Lasso In Aid of Causal Inference](#ate) 4. [Empirical Illustration using `hdm`](#hdm) --- class: title-slide-section-blue, center, middle name: projects # Causal Inference and Treatment Effects --- # The road not taken <img src="figs/roads.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Source: [https://mru.org/courses/mastering-econometrics/ceteris-paribus](https://mru.org/courses/mastering-econometrics/ceteris-paribus) --- # Notation - `\(Y_i\)` is a random variable - `\(X_i\)` is a vector of attributes - `\(\mathbf{X}\)` is a design matrix --- # Treatment and potential outcomes (Rubin, 1974, 1977) - Treatment `$$D_i=\begin{cases} 1, & \text{if unit } i \text{ received the treatment} \\ 0, & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases}$$` -- - Treatment and potential outcomes `$$\begin{matrix} Y_{i0} & \text{is the potential outcome for unit } i \text{ with } D_i = 0\\ Y_{i1} & \text{is the potential outcome for unit } i \text{ with }D_i = 1 \end{matrix}$$` -- - Observed outcome: Under the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA), The realization of unit `\(i\)`'s outcome is `$$Y_i = Y_{1i}D_i + Y_{0i}(1-D_i)$$` -- __Fundamental problem of causal inference__ (Holland, 1986): We cannot observe _both_ `\(Y_{1i}\)` and `\(Y_{0i}\)`. --- # Treatment effect and observed outcomes - Individual treatment effect: The difference between unit `\(i\)`'s potential outcomes: `$$\tau_i = Y_{1i} - Y_{0i}$$` -- - _Average treatment effect_ (ATE) `$$\mathbb{E}[\tau_i] = \mathbb{E}[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}] = \mathbb{E}[Y_{1i}]-\mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}]$$` -- - _Average treatment effect for the treatment group_ (ATT) `$$\mathbb{E}[\tau_i | D_i=1] = \mathbb{E}[Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}| D_i=1] = \mathbb{E}[Y_{1i}| D_i=1]-\mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}| D_i=1]$$` __NOTE:__ The complement of the treatment group is the _control_ group. --- # Selection bias A naive estimand for ATE is the difference between average outcomes based on treatment status However, this might be misleading: `$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0\right] &=\underbrace{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1 i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{0i} | D_{i}=1\right]}_{\text{ATT}} + \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{0 i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{0i} | D_{i}=0\right]}_{\text{selection bias}} \end{aligned}$$` > __Causal inference is mostly about eliminating selection-bias__ __EXAMPLE:__ Individuals who go to private universities probably have different characteristics than those who go to public universities. --- # Randomized control trial (RCT) solves selection bias In an RCT, the treatments are randomly assigned. This means entails that `\(D_i\)` is _independent_ of potential outcomes, namely `$$\{Y_{1i}, Y_{0i}\} \perp D_i$$` RCTs enables us to estimate ATE using the average difference in outcomes by treatment status: `$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i} | D_{i}=0\right] &=\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1 i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{0i} | D_{i}=0\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1 i} | D_{i}=1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_{0 i} | D_{i}=1\right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1 i}-Y_{0 i} | D_{i}=1\right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{1 i}-Y_{0 i}\right] \\ &= \text{ATE} \end{aligned}$$` __EXAMPLE:__ In theory, randomly assigning students to private and public universities would allow us to estimate the ATE going to private school have on future earnings. Clearly, RCT in this case is infeasible. --- # Estimands and regression Assume for now that the treatment effect is constant across all individuals, i.e., `$$\tau = Y_{1i}-Y_{0i},\quad \forall i.$$` Accordingly, we can express `\(Y_i\)` as `$$\begin{aligned} Y_i &= Y_{1i}D_i + Y_{0i}(1-D_i) \\ &= Y_{0i} + D_i(Y_{1i} - Y_{0i}), \\ &= Y_{0i} + \tau D_i, & \text{since }\tau = Y_{1i}-Y_{0i}\\ &= \mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}] + \tau D_i + Y_{0i}-\mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}], & \text{add and subtract } \mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}]\\ \end{aligned}$$` Or more conveniently `$$Y_i = \alpha + \tau D_i + u_i,$$` where `\(\alpha = \mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}]\)` and `\(u_i = Y_{0i}-\mathbb{E}[Y_{0i}]\)` is the random component of `\(Y_{0i}\)`. --- # Unconfoundedness .pull-left[ In observational studies, treatments are not randomly assigned. (Think of `\(D_i = \{\text{private}, \text{public}\}\)`.) In this case, identifying causal effects depended on the _Unconfoundedness_ assumption (also known as "selection-on-observable"), which is defined as `$$\{Y_{1i}, Y_{0i}\} \perp D_i | {X}_i$$` In words: treatment assignment is independent of potential outcomes _conditional_ on observed `\({X}_i\)`, i.e., selection bias _disappears_ when we control for `\({X}_I\)`. ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Adjusting for confounding factors The most common approach for controlling for `\(X_i\)` is by adding them to the regression: `$$Y_i = \alpha + \tau D_i + {X}_i'\boldsymbol{\beta} + u_i,$$` __COMMENTS__: 1. Strictly speaking, the above regression model is valid if we actually _believe_ that the "true" model is `\(Y_i = \alpha + \tau D_i + {X}_i'\boldsymbol{\beta} + u_i.\)` 2. If `\(D_i\)` is randomly assigned, adding `\({X}_i\)` to the regression might increases the accuracy of ATE. 3. If `\(D_i\)` is assigned conditional on `\({X}_i\)` (e.g., in observational settings), adding `\({X}_i\)` to the regression eliminates selection bias. --- # An aside: Bad controls .pull-left[ - Bad controls are variables that are themselves outcome variables. - This distinction becomes important when dealing with high-dimensional data __EXAMPLE:__ Occupation as control in a return to years of schooling regression. Discovering that a person works as a developer in a high-tech firm changes things; knowing that the person does not have a college degree tells us immediately that he is likely to be highly capable. ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Causal inference in high-dimensional setting Consider again the standard "treatment effect regression": `$$Y_i=\alpha+\underbrace{\tau D_i}_{\text{low dimensional}} +\underbrace{\sum_{j=1}^{k}\beta_{j}X_{ij}}_{\text{high dimensional}}+\varepsilon_i,\quad\text{for }i=1,\dots,n$$` Our object of interest is `\(\widehat{\tau}\)`, the estimated _average treatment effect_ (ATE). In high-dimensional settings `\(k \gg n\)`. --- class: title-slide-section-blue, center, middle name: Lasso # Variable Selection Using the Lasso --- # Guarantees vs. guidance - Most (if not all) of what we've done so far is based on _guidance_ - Choosing the number of folds in CV - Size of the holdout set - Tuning parameter(s) - loss function - function class - In causal inference, we need _guaranties_ - variable selection - Confidence intervals and `\(p\)`-values - To get guarantees, we typically need - Assumptions about a "true" model - Asymptotics `\(n\rightarrow\infty\)`, `\(k\rightarrow ?\)` --- # Resources on the theory of Lasso .pull-left[ - [_Statistical Learning with Sparsity - The Lasso and Generalizations_](https://web.stanford.edu/~hastie/StatLearnSparsity/) (Hastie, Tibshirani, and Wainwright), __Chapter 11: Theoretical Results for the Lasso.__ (PDF available online) - [_Statistics for High-Dimensional Data - Methods, Theory and Applications_](https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783642201912) (Buhlmann and van de Geer), __Chapter 7: Variable Selection with the Lasso.__ - [_High Dimensional Statistics - A Non-Asymptotic Viewpoint_](https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/highdimensional-statistics/8A91ECEEC38F46DAB53E9FF8757C7A4E) (Wainwright), __Chapter 7: Sparse Linear Models in High Dimensions__ ] .pull-right[ <img src="figs/sparsebooks3.png" width="100%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Some notation to help you penetrate the Lasso literature Suppose `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)` is a `\(k\times 1\)` vector with typical element `\(\beta_i\)`. - The `\(\ell_0\)`-norm is defined as `\(||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_0=\sum_{j=1}^{k}\boldsymbol{1}_{\{\beta_j\neq0\}}\)`, i.e., the number of non-zero elements in `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)`. - The `\(\ell_1\)`-norm is defined as `\(||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_1=\sum_{j=1}^{k}|\beta_j|\)`. - The `\(\ell_2\)`-norm is defined as `\(||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_2=\left(\sum_{j=1}^{k}|\beta_j|^2\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\)`, i.e., Euclidean norm. - The `\(\ell_\infty\)`-norm is defined as `\(||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_\infty=\sup_j |\beta_j|\)`, i.e., the maximum entries’ magnitude of `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)`. - The support of `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)` , is defined as `\(S\equiv\mathrm{supp}(\boldsymbol{\beta})= \{\beta_j\neq 0 , j=1,\dots,j\}\)`, i.e., the subset of non-zero coefficients. - The size of the support `\(s=|S|\)` is the number of non-zero elements in `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)`, i.e., `\(s=||\boldsymbol{\beta}||_0\)` --- # Recap: Regularized linear regression Typically, the regularized linear regression estimator is given by `$$\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_\lambda = \arg \min_{\boldsymbol{\alpha\in\mathbb{R},\beta}\in\mathbb{R}^{k}}n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n(Y_i-\alpha - {X}_i^{\prime}\boldsymbol{\beta})^2+\lambda R(\boldsymbol{\beta})$$` where | Method| `\(R(\boldsymbol{\beta})\)`| |:--|:--| | OLS | 0 | | Subset selection | `\(\lVert\boldsymbol{\beta}\rVert_0\)` | | __Lasso__ | `\(\lVert\boldsymbol{\beta}\rVert_1\)` | | Ridge | `\(\lVert\boldsymbol{\beta}\rVert_2^2\)` | | Elastic Net | `\(\alpha\lVert\boldsymbol{\beta}\rVert_1 + (1-\alpha)\lVert\boldsymbol{\beta}\rVert_2^2\)` | __NOTE:__ We assume throughout that both `\(Y_i\)` and the elements in `\({X}_i\)` have been standardized so that they have mean zero and unit variance. --- <blockquote class="twitter-tweet" data-lang="he"><p lang="en" dir="ltr">Illustration of the Lasso and its path in 2D: for t small enough, the solution is sparse! <a href="https://t.co/0JV23e32DF">pic.twitter.com/0JV23e32DF</a></p>— Pierre Ablin (@PierreAblin) <a href="https://twitter.com/PierreAblin/status/1107625298936451073?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">March 18 2019</a></blockquote> <script async src="https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js" charset="utf-8"></script> --- # Lasso: The basic setup The linear regression model: `$$Y_{i}=\alpha + X_{i}^{\prime}\boldsymbol{\beta}^{0}+\varepsilon_{i}, \quad i=1,\dots,n,$$` `$$\mathbb{E}\left[\varepsilon_{i}{X}_i\right]=0,\quad \alpha\in\mathbb{R},\quad \boldsymbol{\beta}^0\in\mathbb{R}^k.$$` Under the _exact sparsity_ assumption, only a subset of variables of size `\(s\ll k\)` is included in the model where `\(s \equiv\|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_{0}\)` is the sparsity index. `$$\underbrace{\mathbf{X}_{S}=\left(X_{(1)}, \ldots, X_{\left(s\right)}\right)}_{\text{sparse variables}}, \quad \underbrace{\mathbf{X}_{S^c}=\left(X_{\left(s+1\right)}, \ldots, X_{\left(k\right)}\right)}_{\text{non-sparse variables}}$$` where `\(S\)` is the subset of active predictors, `\(\mathbf{X}_S \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times s}\)` corresponds to the subset of covariates that are in the sparse set, and `\(\mathbf{X}_{S^C} \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times k-s}\)` is the subset of the "irrelevant" non-sparse variables. --- # Evaluation of the Lasso Let `\(\beta^0\)` denote the true vector of coefficients and let `\(\widehat{\beta}\)` denote the Lasso estimator. We can asses the quality of the Lasso in several ways: I. Prediction quality `$$\text{Loss}_{\text{ pred }}\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} ; \boldsymbol{\beta}^{0}\right)=\frac{1}{N}\left\|(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}- \boldsymbol{\beta}^{0})\mathbf{X}^{}\right\|_{2}^{2}=\frac{1}{N}\sum_{j=1}^k\left[(\hat{\beta}_j-\beta^0_j)\mathbf{X}_{(j)}\right]^2$$` II. Parameter consistency `$$\text{Loss}_{\text{param}}\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} ; \boldsymbol{\beta}^{*}\right)=\left\|\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}-\boldsymbol{\beta}^{0}\right\|_{2}^{2}=\sum_{j=1}^k(\hat{\beta}-\beta^0)^2$$` III. Support recovery (sparsistency), e.g., `\(+1\)` if `\(\mathrm{sign}(\beta^0)=\mathrm{sign}(\beta_j)\)`, for all `\(j=1,\dots,k\)`, and zero otherwise. --- # Lasso as a variable selection tool - Variable selection consistency is essential for causal inference. - Lasso is often used as a variable selection tool. - Being able to select the "true" support by Lasso relies on strong assumptions about - the ability to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant variables. - the ability to identify `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)`. --- # Critical assumption #1: Distinguishable sparse betas _Lower eigenvalue_: the min eigenvalue `\(\lambda_{\min }\)` of the sub-matrix `\(\mathbf{X}_S\)` is bounded away from zero. `$$\lambda_{\min }\left(\mathbf{X}_{S}^{\prime} \mathbf{X}^{}_{S} / N\right) \geq C_{\min }>0$$` Linear dependence between the columns of `\(\mathbf{X}_s\)` would make it impossible to identify the true `\(\boldsymbol{\beta},\)` even if we _knew_ which variables are included in `\(\mathbf{X}_S\)`. __NOTE:__ The high-dimension's lower eigenvalue condition replaces the low-dimension's rank condition (i.e., that `\(\mathbf{X}^\prime\mathbf{X}\)` is invertible) --- # Critical assumption #2: Distinguishable active predictors _Irrepresentability condition_ (Zou ,2006; Zhao and Yu, 2006): There must exist some `\(\eta\in[0,1)\)` such that `$$\max _{j \in S^{c}}\left\|\left(\mathbf{X}_{S}^{\prime} \mathbf{X}_{S}\right)^{-1} \mathbf{X}_{S}^{\prime} \mathbf{x}_{j}\right\|_{1} \leq \eta$$` __INTUITION__: What's inside `\(\left\|\cdot\right\|_{1}\)` is like regressing `\(\mathbf{x}_{j}\)` on the variables in `\(\mathbf{X}_s\)` . - When `\(\eta=0\)`, the sparse and non-sparse variables are orthogonal to each other. - When `\(\eta=1\)`, we can reconstruct (some elements of) `\(\mathbf{X}_S\)` using `\(\mathbf{X}_{S^C}\)`. Thus, the irrepresentability condition roughly states that we can distinguish the sparse variables from the non-sparse ones. --- <img src="figs/lassofolds.png" width="55%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Source: [Mullainathan and Spiess (JEP 2017)](https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/jep.31.2.87). --- # Some words on setting the optimal tuning parameter - As we've seen thorough this course, it is also common to choose `\(\lambda\)` empirically, often by cross-validation, based on its predictive performance - In causal analysis, inference and not prediction is the end goal. Moreover, these two objectives often contradict each other (bias vs. variance) - Optimally, the choice of `\(\lambda\)` should provide guarantees about the performance of the model. - Roughly speaking, when it comes to satisfying sparsistency, `\(\lambda\)` is set such that it selects non-zero `\(\beta\)`'s with high probability. --- class: title-slide-section-blue, center, middle name: ate # Lasso in Aid of Causal Inference --- # "Naive" implementation of the Lasso Run `glmnet` ```r glmnet(Y ~ DX) ``` where `DX` is the feature matrix which includes `\(X_i\)` and `\(D_i\)`. The estimated coefficients are: `$$\left(\widehat{\alpha},\widehat{\tau}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=\underset{\alpha, \tau \in \mathbb{R}, \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^{k+1}}{\arg \min } \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\alpha-\tau D_{i}-\boldsymbol{\beta}^{\prime} X_{i}\right)^{2}+\lambda\left(|\tau|+\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left|\beta_{j}\right|\right)$$` __PROBLEMS:__ 1. Both `\(\widehat\tau\)` and `\(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\)` are biased towards zero (shrinkage). 2. Lasso might drop `\(D_i\)`, i.e., shrink `\(\widehat\tau\)` to zero. Can also happen to relevant confounding factors. 3. How to choose `\(\lambda\)`? --- # Toward a solution OK, lets keep `\(D_i\)` in: `$$\left(\widehat{\alpha}, \widehat{\tau}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\prime}\right)^{\prime}=\underset{\alpha,\tau \in \mathbb{R}, \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^{k}}{\arg \min } \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\alpha-\tau D_{i}-\boldsymbol{\beta}^{\prime} X_{i}\right)^{2}+\lambda\left(\sum_{j=1}^{k}\left|\beta_{j}\right|\right)$$` Then, _debias_ the results using "Post-Lasso", i.e, use Lasso for variable selection and then run OLS with the selected variables. __PROBLEMS:__ 1. How to choose `\(\lambda\)`? 2. _Omitted variable bias_: The Lasso might drop features that are correlated with `\(D_i\)` because they are "bad" predictor of `\(Y_i\)`. --- # Problem solved? <img src="figs/naive_Lasso.png" width="55%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Source: [https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf](https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf) --- # Solution: Double-selection Lasso (Belloni, et al., REStud 2013) __First step__: Regress `\(Y_i\)` on `\({X}_i\)` and `\(D_i\)` on `\({X}_i\)`: `$$\begin{aligned} \widehat{\gamma} &=\underset{\boldsymbol{\gamma} \in \mathbb{R}^{p+1}}{\arg \min } \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(Y_{i}-\boldsymbol{\gamma}^{\prime} X_{i}\right)^{2}+\lambda_{\gamma}\left(\sum_{j=2}^{p}\left|\gamma_{j}\right|\right) \\ \widehat{\delta} &=\underset{\boldsymbol{\delta} \in \mathbb{R}^{q+1}}{\arg \min } \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(D_{i}-\boldsymbol{\delta}^{\prime} X_{i}\right)^{2}+\lambda_{\delta}\left(\sum_{j=2}^{q}\left|\delta_{j}\right|\right) \end{aligned}$$` __Second step__: Refit the model by OLS and include the `\(\mathbf{X}\)`'s that are significant predictors of `\(Y_i\)` _and_ `\(D_i\)`. __Third step__: Proceed to inference using standard confidence intervals. > The Tuning parameter `\(\lambda\)` is set such that the non-sparse coefficients are correctly selected with high probability. --- # Does it work? <img src="figs/double_Lasso.png" width="55%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Source: [https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf](https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf) --- # Statistical inference <img src="figs/lassonormal.png" width="55%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Source: [https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf](https://stuff.mit.edu/~vchern/papers/Chernozhukov-Saloniki.pdf) --- # Intuition: Partialling-out regression consider the following two alternatives for estimating the effect of `\(X_{1i}\)` (a scalar) on `\(Y_i\)`, while adjusting for `\(X_{2i}\)`: __Alternative 1:__ Run `$$Y_i = \alpha + \beta X_{1i} + \gamma X_{2i} + \varepsilon_i$$` __Alternative 2:__ First, run `\(Y_i\)` on `\(X_{2i}\)` and `\(X_{1i}\)` on `\(X_{2i}\)` and keep the residuals, i.e., run `$$Y_i = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1 X_{2i} + u^Y_i,\quad\text{and}\quad X_{1i} = \delta_0 + \delta_1 X_{2i} + u^{X_{1}}_i,$$` and keep `\(\widehat{u}^Y_i\)` and `\(\widehat{u}^{X_{1}}_i\)`. Next, run `$$\widehat{u}^Y_i = \beta^*\widehat{u}^{X_{1}}_i + v_i.$$` > According to the [Frisch-Waugh-Lovell (FWV) Theorem](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frisch%E2%80%93Waugh%E2%80%93Lovell_theorem), `$$\widehat\beta = \widehat{\beta}^*.$$` --- # Notes on the guarantees of double-selection Lasso __Approximate Sparsity__ Consider the following regression model: `$$Y_{i}=f\left({W}_{i}\right)+\varepsilon_{i}={X}_{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}^{0}+r_{i}+\varepsilon_{i}, \quad 1,\dots,n$$` where `\(r_i\)` is the approximation error. Under _approximate sparsity_, it is assumed that `\(f\left({W}_{i}\right)\)` can be approximated sufficiently well (up to `\(r_i\)`) by `\({X}_{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}^{0}\)`, while using only a small number of non-zero coefficients. __Restricted Sparse Eigenvalue Condition (RSEC)__ This condition puts bounds on the number of variables outside the support the Lasso can select. Relevant for the post-lasso stage. __Regularization Event__ The tuning parameter `\(\lambda\)` is to a value that it selects to correct model with probability of at least `\(p\)`, where `\(p\)` is set by the user. Further assumptions regarding the quantile function of the maximal value of the gradient of the objective function at `\(\boldsymbol{\beta}^0\)`, and the error term (homoskedasticity vs. heteroskedasticity). See Belloni et al. (2012) for further details. --- # Further extensions of double-selection 1. Chernozhukov et al. (AER 2017): Other function classes ("Double-ML"), e.g., use random forest for `\(Y_i \sim X_i\)` and regularized logit for `\(D_i \sim X_i\)`. 2. Instrumental variables (Belloni et al., Ecta 2012, Chernozhukov et al., AER 2015) 3. Heterogeneous treatment effects (Belloni et al., Ecta 2017) 4. Panel data (Belloni, et al., JBES 2016) --- class: title-slide-section-blue, center, middle name: hdm # Empirical Illustration using `hdm` --- # The `hdm` package<sup>*</sup> ["High-Dimensional Metrics"](https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2016/RJ-2016-040/RJ-2016-040.pdf) (`hdm`) by Victor Chernozhukov, Chris Hansen, and Martin Spindler is an R package for estimation and quantification of uncertainty in high-dimensional approximately sparse models. To install the package: ```r install.packages("hdm") ``` To load the package: ```r library(hdm) ``` .footnote[ [*] There now also a new Stata module named [`Lassopack`](https://stataLasso.github.io/docs/Lassopack/) that includes a rich suite of programs for regularized regression in high-dimensional setting. ] --- # Illustration: Testing for growth convergence The standard growth convergence empirical model: `$$Y_{i,T}=\alpha_{0}+\alpha_{1} Y_{i,0}+\sum_{j=1}^{k} \beta_{j} X_{i j}+\varepsilon_{i},\quad i=1,\dots,n,$$` where - `\(Y_{i,T}\)` national growth rates in GDP per capita for the periods 1965-1975 and 1975-1985. - `\(Y_{i,0}\)` is the log of the initial level of GDP at the beginning of the specified decade. - `\(X_{ij}\)` covariates which might influence growth. The growth convergence hypothesis implies that `\(\alpha_1<0\)`. --- # Growth data To test the growth convergence hypothesis, we will make use of the Barro and Lee (1994) dataset ```r data("GrowthData") ``` The data contain macroeconomic information for large set of countries over several decades. In particular, - `\(n\)` = 90 countries - `\(k\)` = 60 country features Not so big... Nevertheless, the number of covariates is large relative to the sample size `\(\Rightarrow\)` variable selection is important! --- ```r library(tidyverse) GrowthData %>% as_tibble %>% head(2) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 63 ## Outcome intercept gdpsh465 bmp1l freeop freetar h65 hm65 hf65 p65 ## <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 -0.0243 1 6.59 0.284 0.153 0.0439 0.007 0.013 0.001 0.290 ## 2 0.100 1 6.83 0.614 0.314 0.0618 0.019 0.032 0.007 0.91 ## # ... with 53 more variables: pm65 <dbl>, pf65 <dbl>, s65 <dbl>, ## # sm65 <dbl>, sf65 <dbl>, fert65 <dbl>, mort65 <dbl>, lifee065 <dbl>, ## # gpop1 <dbl>, fert1 <dbl>, mort1 <dbl>, invsh41 <dbl>, geetot1 <dbl>, ## # geerec1 <dbl>, gde1 <dbl>, govwb1 <dbl>, govsh41 <dbl>, ## # gvxdxe41 <dbl>, high65 <dbl>, highm65 <dbl>, highf65 <dbl>, ## # highc65 <dbl>, highcm65 <dbl>, highcf65 <dbl>, human65 <dbl>, ## # humanm65 <dbl>, humanf65 <dbl>, hyr65 <dbl>, hyrm65 <dbl>, ## # hyrf65 <dbl>, no65 <dbl>, nom65 <dbl>, nof65 <dbl>, pinstab1 <dbl>, ## # pop65 <int>, worker65 <dbl>, pop1565 <dbl>, pop6565 <dbl>, ## # sec65 <dbl>, secm65 <dbl>, secf65 <dbl>, secc65 <dbl>, seccm65 <dbl>, ## # seccf65 <dbl>, syr65 <dbl>, syrm65 <dbl>, syrf65 <dbl>, ## # teapri65 <dbl>, teasec65 <dbl>, ex1 <dbl>, im1 <dbl>, xr65 <dbl>, ## # tot1 <dbl> ``` --- # Data processing Rename the response and "treatment" variables: ```r GrowthData <- GrowthData %>% rename(YT = Outcome, Y0 = gdpsh465) ``` Transform the data to vectors and matrices (to be used in the `rlassoEffect()` function) ```r YT <- GrowthData %>% select(YT) %>% pull() Y0 <- GrowthData %>% select(Y0) %>% pull() X <- GrowthData %>% select(-c("Y0", "YT")) %>% as.matrix() Y0_X <- GrowthData %>% select(-YT) %>% as.matrix() ``` --- # Estimation of the convergence parameter `\(\alpha_1\)` __Method 1:__ OLS ```r ols <- lm(YT ~ ., data = GrowthData) ``` __Method 2:__ Naive (rigorous) Lasso ```r naive_Lasso <- rlasso(x = Y0_X, y = YT) ``` Does the Lasso drop `Y0`? ```r naive_Lasso$beta[2] ``` ``` ## Y0 ## 0 ``` Unfortunately, yes... --- # Estimation of the convergence parameter `\(\alpha_1\)` __Method 3:__ Partialling out Lasso ```r part_Lasso <- rlassoEffect(x = X, y = YT, d = Y0, method = "partialling out") ``` __Method 4:__ Double-selection Lasso ```r double_Lasso <- rlassoEffect(x = X, y = YT, d = Y0, method = "double selection") ``` --- # Tidying the results ```r # OLS ols_tbl <- tidy(ols) %>% filter(term == "Y0") %>% mutate(method = "OLS") %>% select(method, estimate, std.error) # Naive Lasso naive_Lasso_tbl <- tibble(method = "Naive Lasso", estimate = NA, std.error = NA) # Partialling-out Lasso results_part_Lasso <- summary(part_Lasso)[[1]][1, 1:2] part_Lasso_tbl <- tibble(method = "Partialling-out Lasso", estimate = results_part_Lasso[1], std.error = results_part_Lasso[2]) # Double-sellection Lasso results_double_Lasso <- summary(double_Lasso)[[1]][1, 1:2] double_Lasso_tbl <- tibble(method = "Double-selection Lasso", estimate = results_double_Lasso[1], std.error = results_double_Lasso[2]) ``` --- # Results of the convergence test ```r kable(bind_rows(ols_tbl, naive_Lasso_tbl, part_Lasso_tbl, double_Lasso_tbl), format = "html") ``` <table> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> method </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> estimate </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> std.error </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> OLS </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.0093780 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0298877 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Naive Lasso </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Partialling-out Lasso </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.0498115 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0139364 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Double-selection Lasso </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.0500059 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0157914 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> Double-selection and partialling-out yield much more precise estimates and provide support the conditional convergence hypothesis --- class: .title-slide-final, center, inverse, middle # `slides %>% end()` [<i class="fa fa-github"></i> Source code](https://github.com/ml4econ/notes-spring2019/tree/master/08-lasso-ate) --- # Selected references Ahrens, A., Hansen, C. B., & Schaffer, M. E. (2019). lassopack: Model selection and prediction with regularized regression in Stata. Belloni, A., D. Chen, V. Chernozhukov, and C. Hansen. 2012. Sparse Models and Methods for Optimal Instruments With an Application to Eminent Domain. _Econometrica_ 80(6): 2369–2429. Belloni, A., & Chernozhukov, V. (2013). Least squares after model selection in high-dimensional sparse models. _Bernoulli_, 19(2), 521–547. Belloni, A., Chernozhukov, V., & Hansen, C. (2013). Inference on treatment effects after selection among high-dimensional controls. _Review of Economic Studies_, 81(2), 608–650. Belloni, A., Chernozhukov, V., & Hansen, C. (2014). High-Dimensional Methods and Inference on Structural and Treatment Effects. _Journal of Economic Perspectives_, 28(2), 29–50. --- # Selected references Chernozhukov, V., Hansen, C., & Spindler, M. (2015). Post-selection and post-regularization inference in linear models with many controls and instruments. _American Economic Review_, 105(5), 486–490. Chernozhukov, V., Hansen, C., & Spindler, M. (2016). hdm: High-Dimensional Metrics. _The R Journal_, 8(2), 185–199. Chernozhukov, V., Chetverikov, D., Demirer, M., Duflo, E., Hansen, C., & Newey, W. (2017). Double/debiased/Neyman machine learning of treatment effects. _American Economic Review_, 107(5), 261–265. Mullainathan, S. & Spiess, J., 2017. Machine Learning: An Applied Econometric Approach. _Journal of Economic Perspectives_, 31(2), pp.87–106. --- # Selected references Van de Geer, S. A., & Bühlmann, P. (2009). On the conditions used to prove oracle results for the lasso. _Electronic Journal of Statistics_, 3, 1360–1392. Zhao, P., & Yu, B. (2006). On Model Selection Consistency of Lasso. _Journal of Machine Learning Research_, 7, 2541–2563.