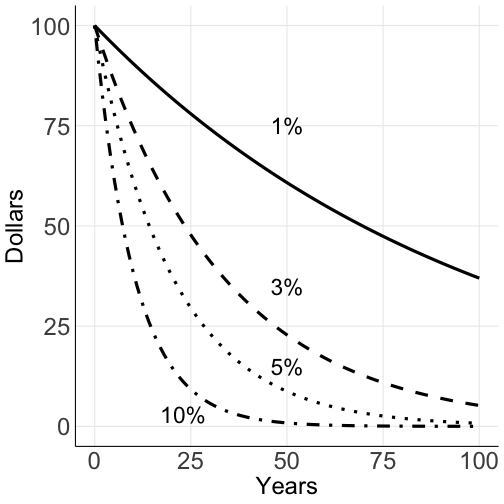

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Lecture 09 ] .subtitle[ ## Discounting and Cost Benefit Analysis ] .author[ ### Ivan Rudik ] .date[ ### AEM 4510 ] --- exclude: true ```r if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman") ``` ``` ## Loading required package: pacman ``` ```r pacman::p_load( tidyverse, xaringanExtra, rlang, patchwork, nycflights13, tweetrmd, vembedr ) options(htmltools.dir.version = FALSE) knitr::opts_hooks$set(fig.callout = function(options) { if (options$fig.callout) { options$echo <- FALSE } knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, fig.align="center") options }) ``` ``` ## Warning: 'xaringanExtra::style_panelset' is deprecated. ## Use 'style_panelset_tabs' instead. ## See help("Deprecated") ``` ``` ## Warning in style_panelset_tabs(...): The arguments to `syle_panelset()` changed in xaringanExtra 0.1.0. Please ## refer to the documentation to update your slides. ``` --- # Roadmap 1. What is discounting? 2. What determines the discount rate? 3. What are the implications of discounting on computing the costs and benefits of policies? --- class: inverse, center, middle name: tradable permits # Discounting <html><div style='float:left'></div><hr color='#EB811B' size=1px width=796px></html> --- # Motivating discounting: http://impactlab.org/map At the end of the century we will have much more hot days in some places <center> <img src="files/09-climate-change.png" width="100%" /> </center> --- # Motivating discounting: http://impactlab.org/map At the end of the century we will have much fewer freezing days in others <center> <img src="files/09-climate-change2.png" width="100%" /> </center> --- # Motivating discounting: http://impactlab.org/map This has massive implications for mortality <center> <img src="files/09-climate-damage.png" width="100%" /> </center> --- # Motivating discounting Some places are expecting to have huge gains in GDP from mortality risk -- Others are expecting to have huge losses -- This is all happening in 60-80 years -- How do we compare these costs and benefits to those incurred today? -- We use a .hi[discount rate:] a value that tells us how much future dollars are worth in today's terms --- # A simple example Let `\(r\)` be the discount rate, so `\(\beta = {1 \over 1+r}\)` is the discount factor Suppose we are considering two different projects that have costs and benefits that accrue differently over time | Year | Project A Cost | Project A Benefit | Project B Cost | Project B Benefit | |------|----------------|------------------|----------------|------------------| | 0 | 10000 | 0 | 6000 | 0 | | 1 | 1000 | 4000 | 0 | 1000 | | 2 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | | 3 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | Project A has higher costs and benefits in nominal terms --- # A simple example | Year | Project A Cost | Project A Benefit | Project B Cost | Project B Benefit | |------|----------------|------------------|----------------|------------------| | 0 | 10000 | 0 | 6000 | 0 | | 1 | 1000 | 4000 | 0 | 1000 | | 2 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | | 3 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | **Project A:** `\(PV_A = \frac{4000}{1.05^1} + \frac{4000}{1.05^2} + \frac{4000}{1.05^3} - \frac{10000}{1.05^0} - \frac{1000}{1.05^1} = -59.39\)` **Project B:** `\(PV_B = \frac{1000}{1.05^1} + \frac{3000}{1.05^2} + \frac{3000}{1.05^3} - \frac{6000}{1.05^0} = 264.98\)` --- # What if the discount rate was 3%? | Year | Project A Cost | Project A Benefit | Project B Cost | Project B Benefit | |------|----------------|------------------|----------------|------------------| | 0 | 10000 | 0 | 6000 | 0 | | 1 | 1000 | 4000 | 0 | 1000 | | 2 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | | 3 | 0 | 4000 | 0 | 3000 | **Project A:** `\(PV_A = \frac{4000}{1.03^1} + \frac{4000}{1.03^2} + \frac{4000}{1.03^3} - \frac{10000}{1.03^0} - \frac{1000}{1.03^1} = 343.57\)` **Project B:** `\(PV_B = \frac{1000}{1.03^1} + \frac{3000}{1.03^2} + \frac{3000}{1.03^3} - \frac{6000}{1.03^0} = 544.09\)` --- # Discounting Discounting results in us placing less value on costs and benefits that accrue in the future A dollar 1 year from now is worth `\(\beta = \frac{1}{1+r}\)` dollars today The timing of costs and benefits of projects can then sway which project has greater present value --- # Return to Manne-Richels We ignored the idea of discounting in our discussion of the Manne-Richels model -- Our new problem with discounting is then: -- `$$\min_{a_1} E[TC] = \underbrace{\frac{1}{2}a_1^2}_{\text{current cost}} + \beta\left[(1-p)\times \underbrace{0}_{\text{good state cost}} + p \times \underbrace{\frac{1}{2}(1-a_1)^2}_{\text{bad state cost}}\right]$$` --- # Return to Manne-Richels The first-order condition is: `$$\frac{d E[TC]}{da_1} = a^*_1 - \beta p(1-a^*_1) = 0$$` -- This gives us that: `$$a^*_1 = \frac{\beta p}{1+\beta p}$$` -- How does discounting affect our decisionmaking? --- # Discounting and decisionmaking `$$a^*_1 = \frac{\beta p}{1+\beta p}$$` -- First, notice as `\(r \rightarrow \infty\)` we have `\(\beta = {1 \over 1 + r} \rightarrow 0\)`, we put less and less weight on the future -- This means we do less abatement today in period 1! -- That's intuitive, let's see what discount actually looks like graphically -- What is the value of a future payment of $100? --- # PV of $100 .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Higher discount rates place less value on future benefits Things > 30 years in the future have basically no value with a 10% discount rate At a 1% discount rate we value things 100 years in the future at almost half their value today ] --- # Discounting Why does this matter? -- Lots of things (like climate change) have costs or benefits that occur .hi[far] in the future -- e.g. the benefits of taking action against climate change will be mostly borne by future generations, decades from now -- Depending on our choice of discount rate these costs and benefits can be substantial or trivial --- # Discounting 1 million in damages in 200 years at a discount rate of r = 2% is worth 19,053 today -- 1 million in damages in 200 years at a discount rate of r = 8% is worth only 21 cents today -- 5 orders of magnitude difference! -- This makes the choice of the discount rate one of the most important (and contentious) things about climate change policy --- # Discounting: how do we choose? How do we choose the discount rate? -- .hi[Option 1:] take the market rate -- This is just the real interest paid on certain investments -- In a perfect market equilibrium, it is the productivity of capital -- Why might this not be the rate we want to choose as a regulator? --- # Discounting: how do we choose? Issues with market rates: -- Market rates don't reflect externalities -- Super-responsibility of government: the government represents future generations as well as current generations (only current ones are represented in the market) -- Dual-role of individuals: in political roles, people are more concerned about future generations than in their day-to-day behavior which determines the market rate --- # Discounting: how do we choose? .hi[Option 2:] social discounting -- With social discounting we determine the discount rate from economic and ethical considerations -- Why should we discount the future? -- First, .hi[time]: people are impatient -- And .hi[growth/inequality]: all else equal, if someone is richer in 10 years, a dollar is worth more to them today than in 10 years (in utility terms) --- # Ramsey Discounting With a decent amount of math we can write the social discount rate `\(r\)` as a function of three terms: `$$r = \delta + \eta \times g$$` -- `\(\delta\)` is called the .hi[pure rate of time preference] or .hi[utility discount rate]: how much do we value future *utility* -- `\(\eta\)` is the .hi[elasticity of marginal utility]: how quickly does marginal utility (benefit) decline in consumption (how severe are diminishing marginal returns)? -- `\(g\)` is the .hi[growth rate]: how fast does consumption grow over time? --- # Ramsey Discounting Here's some alternative descriptions of how to think about these terms: -- `\(\delta\)`: how much is 1 util tomorrow worth today? -- `\(\eta\)`: how much do we value poorer vs richer times/generations? Bigger `\(\eta\)` `\(\rightarrow\)` more averse to inequality over time - `\(\eta = - \frac{\partial U'(X)}{\partial X}{X \over U'(X)} = - U''(X){X \over U'(X)}\)`, by how many percent does marginal utility `\(U'(X)\)` change if consumption changes by 1% -- `\(g\)`: how rich will we / future generations be compared to today? --- # Ramsey Discounting `$$r = \delta + \eta \times g$$` What this means is that if we have values for `\(r\)`, `\(\eta\)`, and `\(g\)`, we can compute the "correct" discount rate from a social perspective -- How do we get values for these terms? -- Two common approaches: descriptive and prescriptive --- # Ramsey Discounting: the descriptive approach The descriptive approach aims to calibrate the discount rate to the real world -- We can observe `\(g\)` in the data / forecasts -- We can sometimes estimate `\(\eta\)` from observed behavior over time -- Once we pick a `\(\delta\)` we have our discount rate `\(r\)` -- The descriptive approach generally chooses `\(\delta\)` so `\(r\)` matches market rates -- Most philosophers and economists would probably not prescribe the descriptive approach --- # Ramsey Discounting: the prescriptive approach First we decide on the 'correct' level of `\(\delta\)` and `\(\eta\)` -- Then we observe `\(g\)` in the data / forecasts -- That gives us `\(r\)` --- # What's the utility discount rate? Both approaches depend on us choosing `\(\delta\)` -- What is the right value for `\(\delta\)`? This is a philosophical question. -- Ramsey (1928): placing different weights upon the utility of different generations is ‘ethically indefensible' -- Harrod (1948): discounting utility represented a 'polite expression for rapacity and the conquest of reason by passion' -- The above arguments are ethical arguments, so are typically used by those favoring the prescriptive approach --- # What's the discount rate? Descriptive The descriptive approach often results in `\(\delta\)` being between 2-3% from reverse engineering the observed market rates -- `\(\eta\)` is then often engineered to be between 1 and 4 -- `\(g\)` is observed and generally between 1 and 3% -- Thus the discount rate usually lies between 2 and 7% -- Quick example: `\(\delta = 2\%, \eta = 2, g = 2\% \rightarrow r = 6\%\)` --- # What's the discount rate? Prescriptive The prescriptive approach often results in `\(\delta\)` being zero or nearly zero for the ethical reasons described above --- # What's the discount rate? Prescriptive Choosing `\(\eta\)` also conveys ethical choices: how do we weigh the distribution of consumption across generations Recall: `\(r = \delta + \eta g\)` -- - `\(\eta = 0\)`: consumption in the future doesn't change our willingness to save/invest today (r is independent of g) -- - `\(\eta\)` is large: if there is positive growth, we are .hi[less] likely to invest in the future (future generations will be rich anyway) -- - `\(\eta\)` is large: if there is negative growth, we are .hi[more] likely to invest in the future (future generations will be poorer than today) --- # Distributive justice Rawls' theory of justice applied here would set `\(\delta = 0\)` and `\(\eta = \infty\)`: fairness for all -- More egalitarian perspectives with respect to: .hi[time] -- yields a smaller `\(\delta\)` and `\(r\)` -- .hi[intergenerational inequality] -- yields a larger `\(\eta\)` and larger `\(r\)` if growth is positive --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-1.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-2.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-3.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-4.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-5.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # What do the experts think? Drupp et al. (2018) <center> <img src="files/10-experts-6.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # Discount rates are being significantly revised <center> <img src="files/10-discounting-1.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # Discount rates are being significantly revised <center> <img src="files/10-discounting-2.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # Discount rates are being significantly revised <center> <img src="files/10-discounting-3.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # Discount rates are being significantly revised <center> <img src="files/10-discounting-4.png" width="70%" /> </center> --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run How should we think about discounting in the .hi[very] long run? -- 100, 100, 300 years into the future when we expect climate change impacts to be their worst? -- Giglo, Maggiori, and Stroebel (2015) come up with a clever way to think about discount rates in the far future: looking at UK and Singaporean housing markets --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run In the UK and Singapore, properties are acquired via .hi[leasehold] or .hi[freehold] -- - .hi[Leasehold:] temporary, pre-paid, tradable ownership contracts with maturities of 99-999 years, once it expires, you lose the property -- - .hi[Freeholds:] same, but **perpetual** ownership, you never lose the property - Similar to how things work in the US --- # Property prices, what do they tell us? Imagine there are two properties A and B, identical in every way except A is a leasehold with 500 years left until maturity and B is a freehold Suppose we observe A selling for 900,000 dollars and B selling for 1,000,000 dollars What do these prices mean? What value do they capture? -- Let's think about a simple example: you are a real estate investor deciding on purchasing a property to add to your rental portfolio in a competitive property market --- # Property prices, what do they tell us? A property makes sense to buy if its cost is less than its benefits -- Houses are kind of like annuities: - Pay an upfront cost (mortgage) - Get a future stream of revenues (rental payments from renters) -- Suppose buyers were competing for a property that has a net present value of $900,000, what market price would we expect someone to pay for this? -- .hi[$900,000!] investors will compete, bidding higher and higher prices until it reaches the benefits of owning the property (same logic as why prices are the MB of regular goods in competitive markets) --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run The price of a house tells us the present value of the future stream of rental payments! -- Now let's go back to the original example: -- Suppose we observe A selling for 900,000 dollars and B selling for 1,000,000 dollars What does the price difference between the two properties tell us? --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run Both properties are identical until year 500 when .hi-blue[poof], -- you no longer own property A but you still own property B -- The difference in prices is telling us the present value of property B rental payments starting .hi[500 years from now] -- The prices tell us about how the market discounts cash flows very, very far in the future, outside anyone's expected lifespan --- # Why do discount rates change over time? Discount rates for cash flows this year versus 500 years in the future may be different for a lot of reasons -- - .hi[Changes in growth:] if growth slows down (e.g. from climate change), discount rates fall - The future is getting richer slower, so the future's marginal value of a dollar is higher than if growth did not slow -- - .hi[Uncertainty:] if we are uncertain about future economic conditions determining the discount rate (e.g. climate change), the discount rate we should use is lower than the average (expected) discount rate --- # Why do discount rates change over time? Let's get a sense of how uncertainty over the proper discount rate matters -- Suppose a hypothetical public transit project is going to impose 1 trillion dollars of costs in 100 years -- Suppose the pure rate of time preference `\(\delta = 1\%\)`, and the elasticity of marginal utility `\(\eta = 1\)` so that the discount rate `\(r = 1\% + 1 \times g\)` -- We think that in 100 years economic growth will either be 0% or 6%, each with 50% chance, (because we are uncertain about the extent of climate change) -- What are the current expected costs of the project? --- # Why do discount rates change over time? The current expected costs are just the costs averaged over either of the potential real discount rates: $$\frac{1}{2} \frac{\$1 \text{ trillion}}{1.01^{100}} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\$1 \text{ trillion}}{1.07^{100}} = \$185 \text{ billion}$$ -- Now lets compute the value of the damages if we used the expected discount rate, the average of the two: 4% $$\frac{\$1 \text{trillion}}{1.04^{100}} = \$20 \text{ billion}$$ --- # Why do discount rates change over time? The expected discount rate of 4% generated costs that were 10 times smaller than the actual costs! This means that the expected discount rate is too high compared to the actual discount rate we should be using if we are uncertain about future discount rates -- What discount rate should we use? -- $$\frac{\$1 \text{ trillion}}{(1+r)^{100}} = \$185 \text{ billion} \qquad \rightarrow r = .017=1.7\%$$ --- # Why do discount rates change over time? If we expected the future discount rate to be either 1% or 7%, the proper discount rate to use was actually 1.7%, .hi[not] the average 4%! -- 1.7% is called the .hi[certainty-equivalent] discount rate: the certain discount rate that delivers the same present value as the possible set of uncertain rates (1% and 7%) -- .hi[Main takeaway:] Uncertainty about the future economic conditions governing the discount rate makes the discount rate we should be using lower than expected --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run: United Kingdom .pull-left[ What are these long run discount rate? In the UK: - leases expiring within 100 years cost 17% less than a freehold - leases expiring 150-300 years from now cost 5% less Implies a discount rate of about .hi[2.6%] ] .pull-right[ <img src="files/10-long-run-discount-1.png" width="100%" /> ] --- # Discount rates in the (very) long run: Singapore .pull-left[ What are these long run discount rate? In Singapore: - leases expiring within 70 years cost 40% less than a freehold - leases expiring 95-99 years from now cost 15% less Implies a discount rate of about .hi[2.6%] ] .pull-right[ <img src="files/10-long-run-discount-2.png" width="100%" /> ] --- # Discount rates on rental payments We can check the validity of these estimates by seeing whether .hi[rental payments] depend on the length remaining of the contract -- There's no reason the rent you pay for your house should depend on how much longer the owner has property rights if your lease is short --- # Discount rates on rental payments .pull-left[ Rental rates (mostly) do not depend on the remaining lease time! ] .pull-right[ <img src="files/10-long-run-discount-3.png" width="100%" /> ]