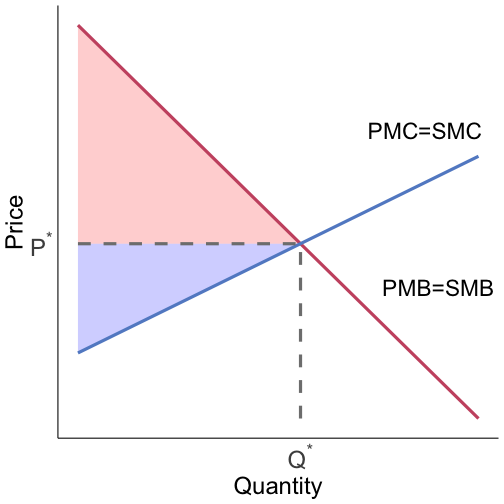

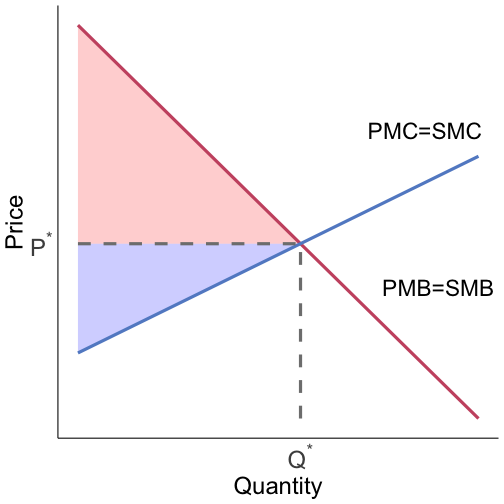

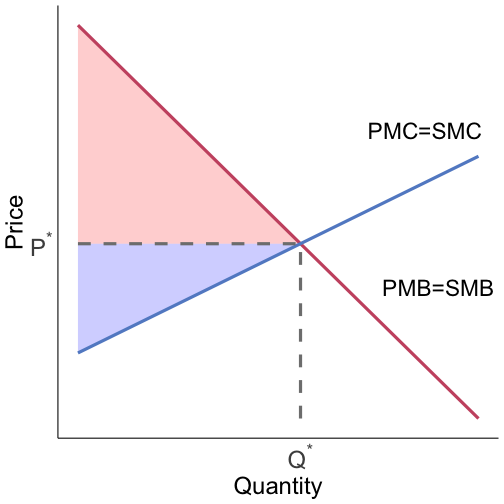

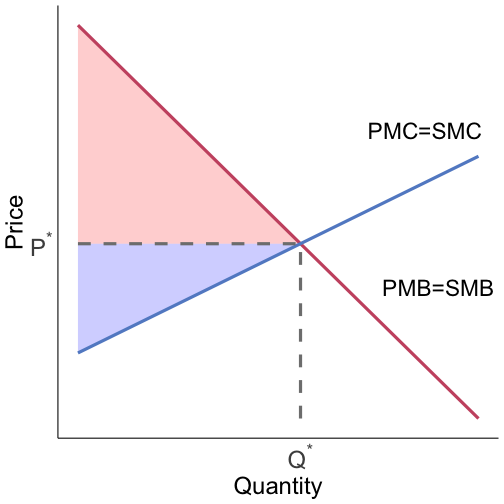

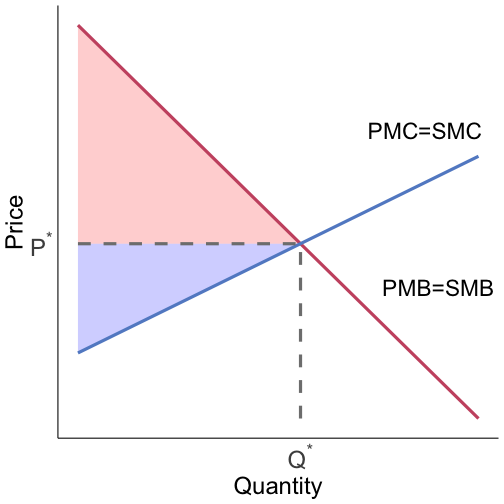

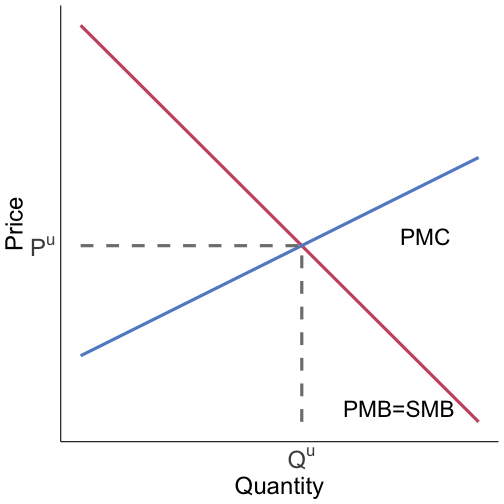

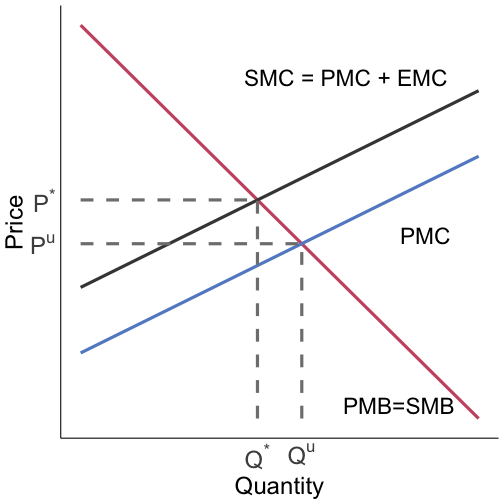

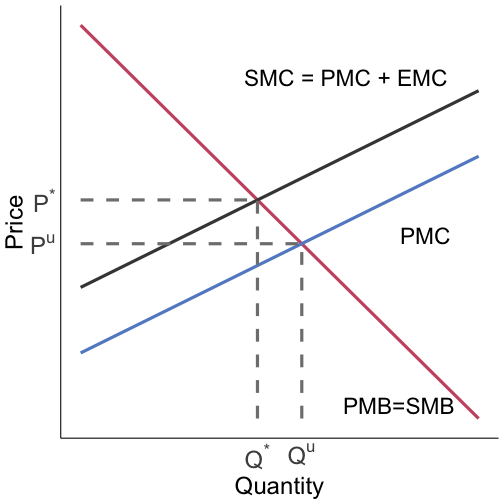

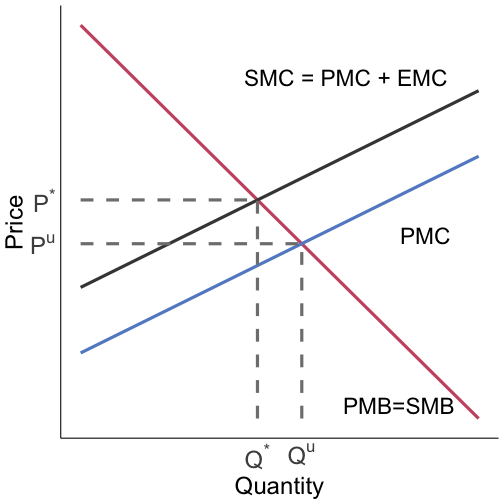

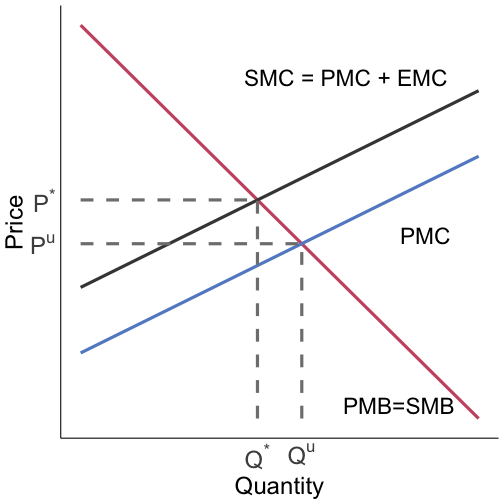

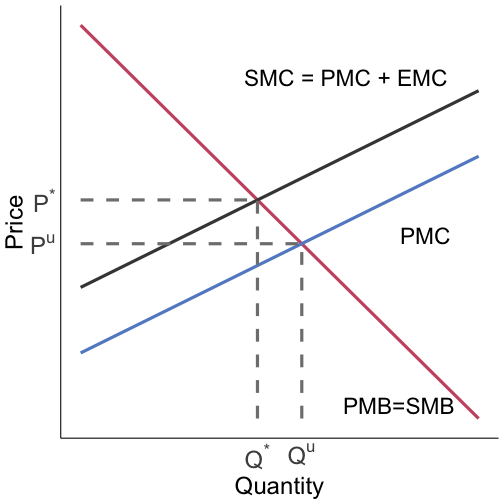

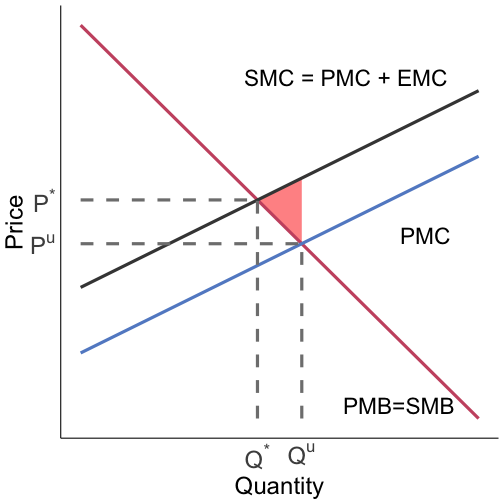

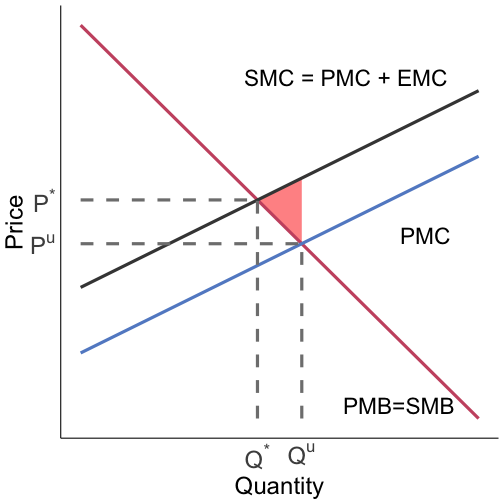

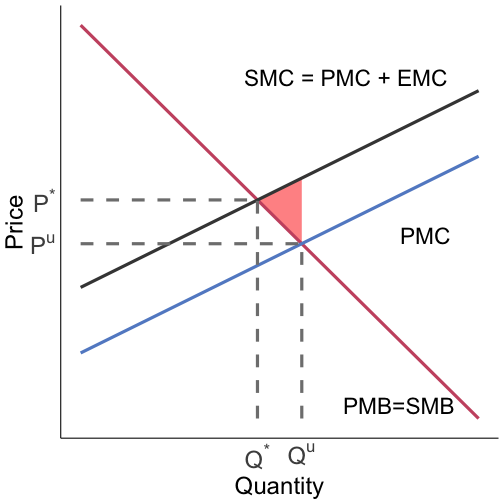

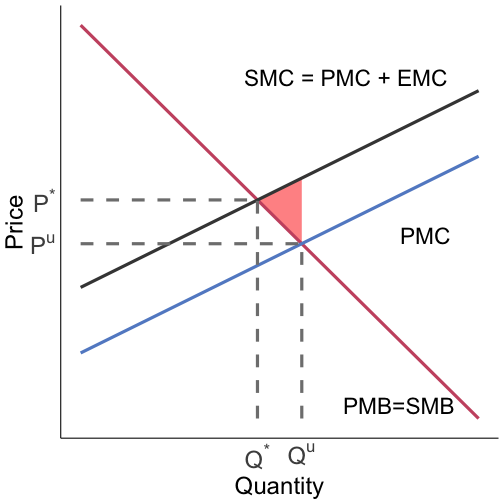

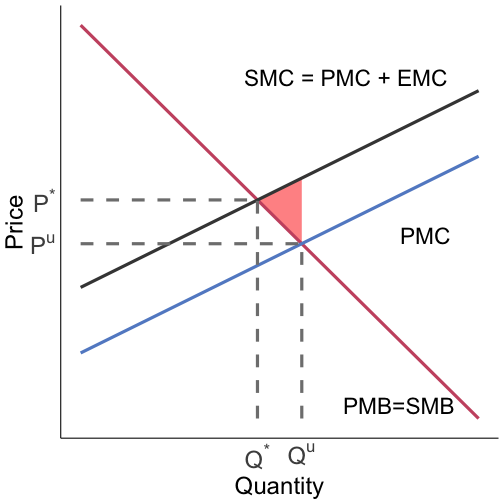

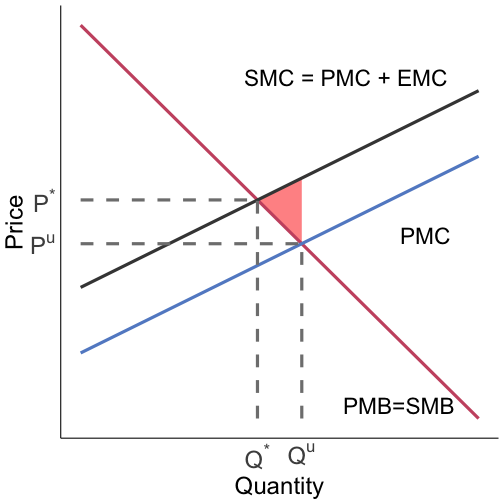

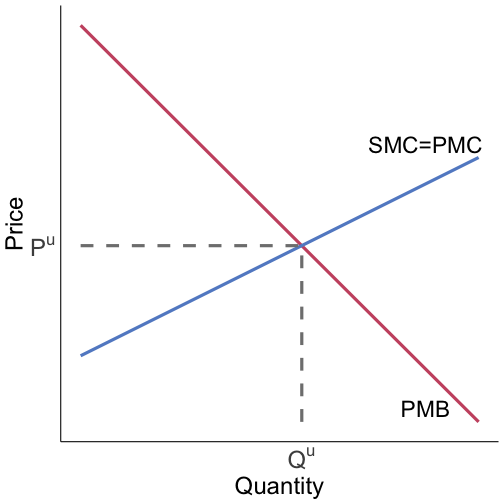

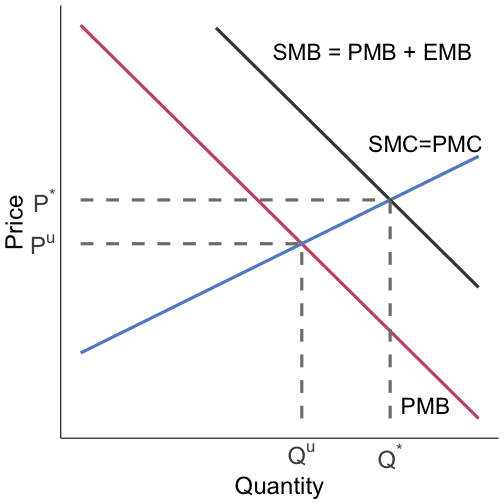

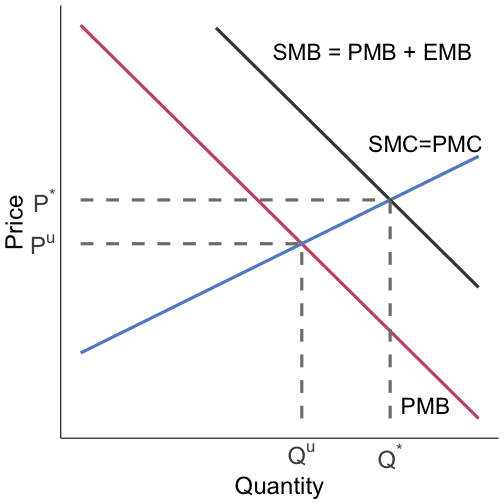

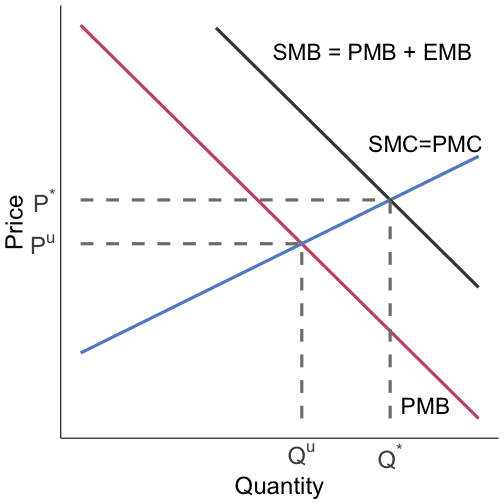

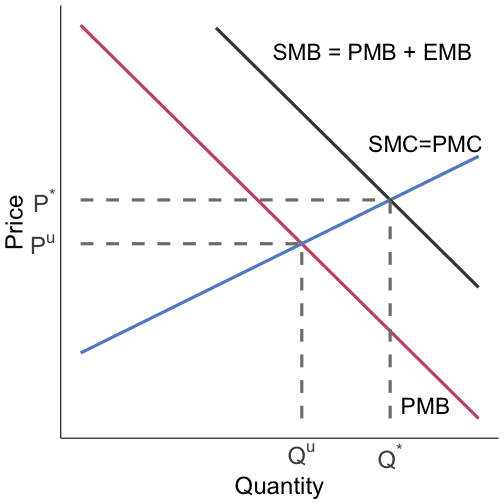

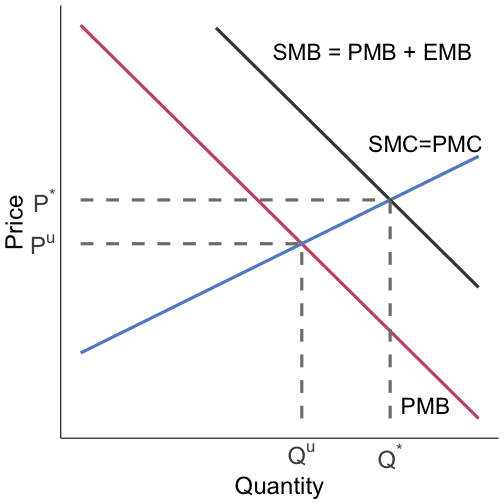

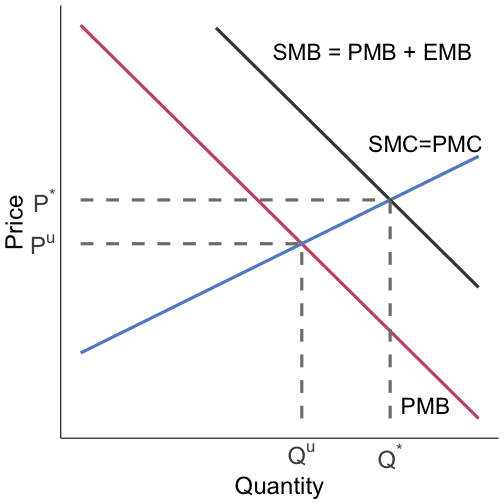

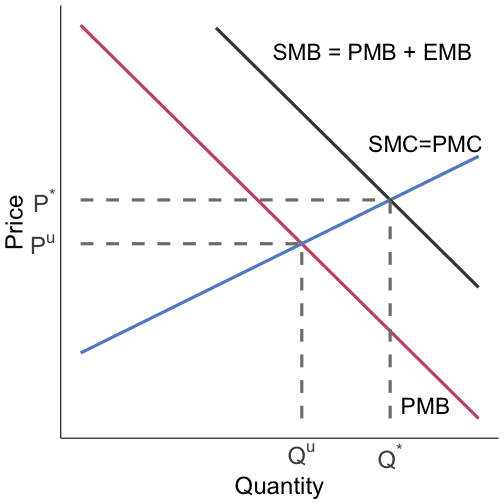

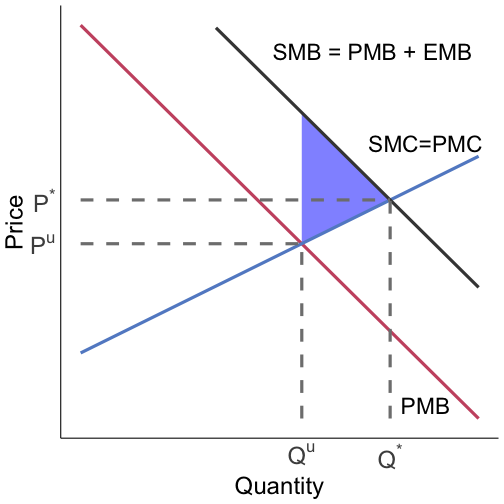

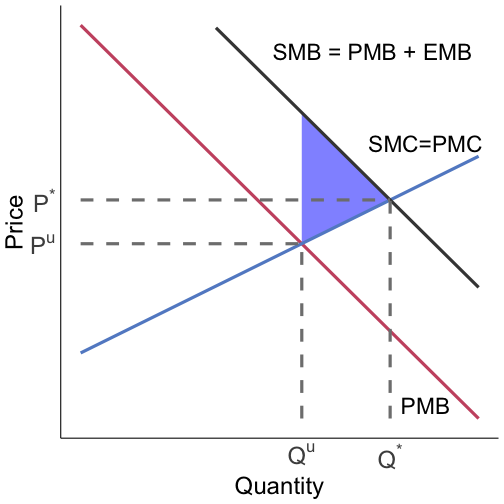

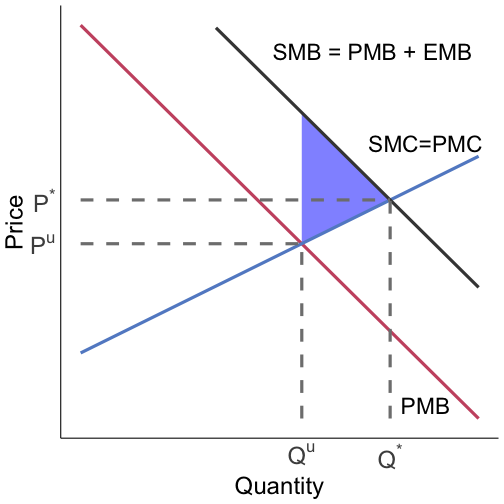

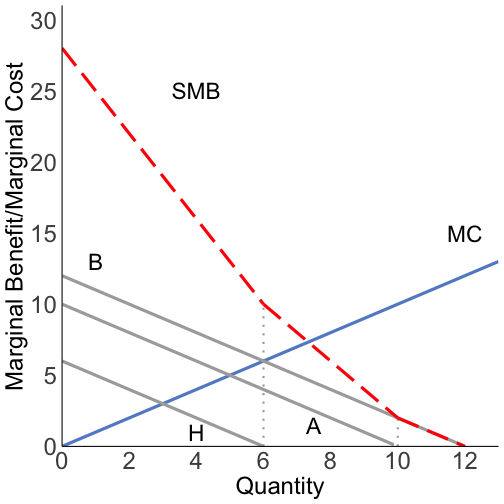

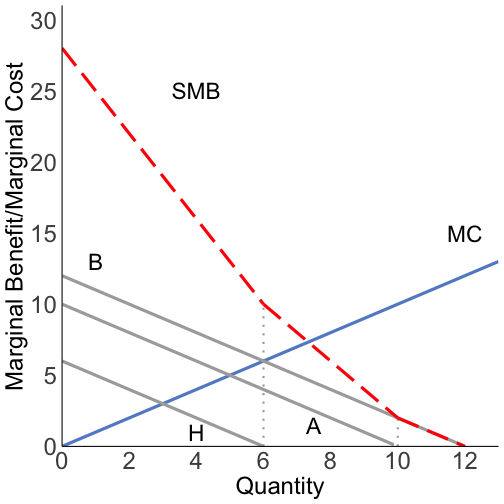

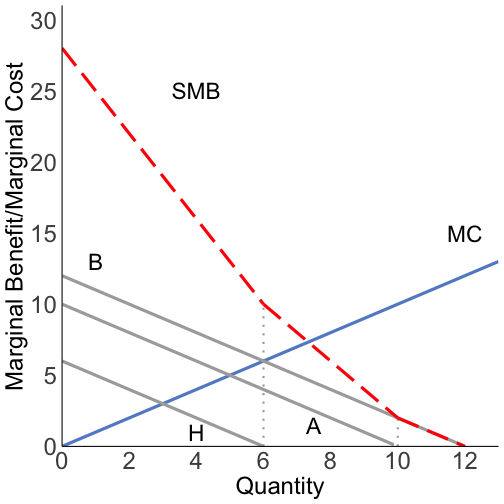

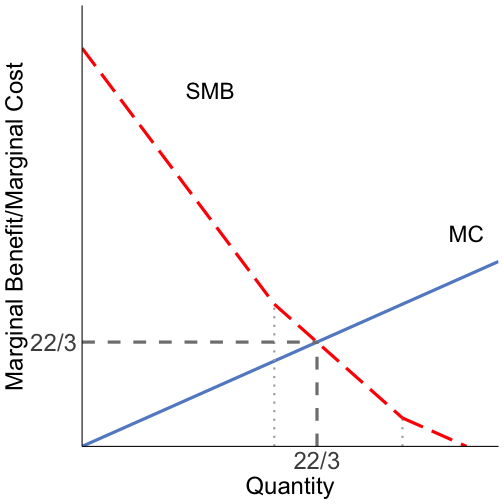

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Lecture 02 ] .subtitle[ ## Market Failures ] .author[ ### Ivan Rudik ] .date[ ### AEM 4510 ] --- exclude: true ```r if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman") pacman::p_load( tidyverse, xaringanExtra, rlang, patchwork, nycflights13, tweetrmd, vembedr ) options(htmltools.dir.version = FALSE) knitr::opts_hooks$set(fig.callout = function(options) { if (options$fig.callout) { options$echo <- FALSE } knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, fig.align="center") options }) ``` ``` ## Warning: 'xaringanExtra::style_panelset' is deprecated. ## Use 'style_panelset_tabs' instead. ## See help("Deprecated") ``` ``` ## Warning in style_panelset_tabs(...): The arguments to `syle_panelset()` changed in xaringanExtra 0.1.0. Please refer to the documentation to update your slides. ``` --- # Roadmap - What are market failures? - When do they happen? - What are the consequences? --- class: inverse, center, middle name: what_is_enviro # Market failures and the environment <html><div style='float:left'></div><hr color='#EB811B' size=1px width=796px></html> <!-- --- --> <!-- # The ideal world: mathematical --> <!-- In the best case scenario, a market equilibrium leads to the efficient allocation --> <!-- -- --> <!-- Example: bread --> <!-- -- --> <!-- Household gets utility `\(U(B,C)\)` from consuming bread `\(B\)` and electricity `\(C\)` --> <!-- -- --> <!-- Price of bread is `\(p_b\)`, price of electricity is `\(p_e\)`, household has a budget `\(Y\)` --> <!-- -- --> <!-- Household solves: --> <!-- \begin{align} --> <!-- &\max_{B,E} U(B,E) \quad \text{subject to: } \quad p_b B + p_e E = Y \\ --> <!-- &\max_{B} U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right) --> <!-- \end{align} --> <!-- --- --> <!-- # The ideal world: mathematical --> <!-- \begin{align} --> <!-- \max_{B} U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right) --> <!-- \end{align} --> <!-- The first-order condition gives us what defines the utility maximizing choice of bread: --> <!-- `$$\frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right)}{\partial B} + \frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right)}{\partial E}\left(- \frac{p_b}{p_e} \right) = 0$$` --> <!-- `$$\frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right)}{\partial B} \Bigg/\frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_e}\right)}{\partial E}= \frac{p_b}{p_e}$$` --> <!-- --- --> <!-- # The ideal world: mathematical --> <!-- `$$\frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_c}\right)}{\partial B} \Bigg/\frac{\partial U\left(B,\frac{Y - p_b B}{p_c}\right)}{\partial C}= \frac{p_b}{p_c}$$` --> <!-- .hi[Left hand side:] marginal rate of substitution (slope of indifference curve between bread and electricity) --> <!-- .hi[Right hand side:] relative prices (slope of budget constraint) --> <!-- -- --> <!-- Households consume the bundle of goods that makes their indifference curve tangent to the budget constraint --> --- # The ideal world: graphical In the best case scenario, a market equilibrium leads to the efficient allocation -- Example: bread -- We have a private bread supply curve (private MC) -- We have a private bread demand curve (private MB) -- In equilibrium: supply = demand so PMC = PMB = price -- For bread, the private costs and benefits are very likely the social costs and benefits --- # Market equilibrium .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Consumer surplus] is the difference between willingness to pay (demand) and price .hi-blue[Producer surplus] is the difference between price and marginal cost (supply) .hi[Total surplus] is the sum of CS and PS ] --- # Market equilibrium .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ For bread, the private costs and benefits are very likely the social costs and benefits What does this mean about the market allocation? ] --- # Market equilibrium .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The market allocation is .hi-blue[efficient] because SMC = SMB Why? ] --- # Market equilibrium .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The market allocation is .hi-blue[efficient] because SMC = SMB Why? Consider deviating from `\((P^*, Q^*)\)` ] --- # Market equilibrium .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Cost of next unit after `\(Q^*\)` > benefit Benefit of last unit `\(\geq\)` cost of last unit before `\(Q^*\)` Competitive market allocations are efficient for private goods ] --- class: inverse, center, middle name: what_is_enviro # Externalities <html><div style='float:left'></div><hr color='#EB811B' size=1px width=796px></html> --- # Externalities If the world was just competitive markets, private goods, no third-parties, there would be no reason to do anything after Econ 101 -- That's not the case in the real world -- In the real world we have .hi-blue[externalities] > An externality exists whenever an individual or firm undertakes an action that impacts another individual or firm in an unintended way for which the latter is not compensated (a negative externality), or for which the latter does not pay (a positive externality) --- # Externalities What is problem with externalities for market outcomes and efficiency? -- There is not a market for the externality -- E.g. at Wegmans or Agway you will not find some important goods on sale: -- - Cleaner air outside -- - Biodiversity in the Amazon -- The central problem is that there are goods that are .hi-red[not priced], why is this a problem? -- Markets rely on prices to signal the social value of goods --- # No markets lead to issues in the Southwest <div class="vembedr" align="center"> <div> <iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/yRUs_gLgpx4" width="533" height="300" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="" data-external="1"></iframe> </div> </div> --- # Externalities: several classifications We can classify externalities in a few ways: -- .hi[Production externalities:] -- generated by a firm in the process of producing some output (e.g. pollution, innovation) -- .hi[Consumption externalities:] -- generated by an individual in the process of consuming an output (e.g. congestion, vaccination) -- .hi-red[Negative externalities:] -- imposes external **costs** (e.g. pollution) -- .hi-blue[Positive externalities:] -- imposes external **benefits** (e.g. vaccination) --- # Negative externalities: what is this? <center> <img src="files/02-ddt.jpg" width="100%" /> </center> --- # Negative externalities: DDT, shockingly bad for you .pull-left[ <img src="files/02-ddt2.png" width="100%" /> ] .pull-right[ DDT is a chemical that was was widely used as an insecticide in the early-mid 1900s Widely used to eradicate Typhus and Malaria Used to treat lice ] --- # Negative externalities: DDT, gives you cancer .pull-left[ <img src="files/02-ddt2.png" width="100%" /> ] .pull-right[ > A relationship between DDT exposure and reproductive effects in humans is suspected, based on studies in animals. In addition, some animals exposed to DDT in studies developed liver tumors. As a result, today, DDT is classified as a probable human carcinogen. ] --- # The birth of the environmental movement <div class="vembedr" align="center"> <div> <iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/kwb6OvvxMjg" width="533" height="300" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="" data-external="1"></iframe> </div> </div> --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal cost (SMC)] is the sum of private marginal cost (PMC) and the external marginal cost (EMC) Where is the SMC? ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal cost (SMC)] is the sum of private marginal cost (PMC) and the external marginal cost (EMC) The PMC curve only reflects the **private costs** of making the DDT It does not account for the external health and wildlife costs ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal costs together gives us the SMC, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal costs together gives us the SMC, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective The unregulated market gives us `\((P^u,Q^u)\)` as an outcome when we want `\((P^*,Q^*)\)` ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal costs together gives us the SMC, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective The unregulated market gives us `\((P^u,Q^u)\)` as an outcome when we want `\((P^*,Q^*)\)` What's the social cost of this market failure? ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Negative externalities generate deadweight loss equal to... ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Negative externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-red[red] area ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Negative externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-red[red] area This is the difference in SMC and SMB for units bought/sold where SMC > SMB: Total SMC - SMB from `\(Q^*\)` to `\(Q^u\)` ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Negative externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-red[red] area This is the difference in SMC and SMB for units bought/sold where SMC > SMB This is the loss to society caused by the externality in the unregulated private market ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Key takeaway: ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Key takeaway: The private market produces too much DDT ] --- # Negative externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Key takeaway: The private market produces too much DDT The private actors are not accounting for the .hi[external costs] they are imposing on people who are not in the DDT transaction (e.g. third parties whose health is being affected) ] --- # Estimating marginal damages with EZ-Pass <div class="vembedr" align="center"> <div> <iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/JLHXYTbSQZY" width="533" height="300" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="" data-external="1"></iframe> </div> </div> --- # Positive externalities <center> <img src="files/02-herd-immunity.png" width="50%" /> </center> --- # Positive externalities .pull-left[ <img src="files/02-mask.jpg" width="100%" /> ] .pull-right[ Vaccines and masks are examples of good with positive externalities You getting or using them has benefits for other people not involved in your vaccine or mask transaction ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal benefit (SMB)] is the sum of private marginal benefit (PMB) and the external marginal benefit (EMB) Where does the SMB curve lie? ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal benefit (SMB)] is the sum of private marginal benefit (PMB) and the external marginal benefit (EMB) ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal benefit (SMB)] is the sum of private marginal benefit (PMB) and the external marginal benefit (EMB) The PMB curve only reflects the **private benefits** of getting a vaccine ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ .hi-red[Social marginal benefit (SMB)] is the sum of private marginal benefit (PMB) and the external marginal benefit (EMB) The PMB curve only reflects the **private benefits** of getting a vaccine It does not account for the external herd immunity benefits ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal benefits together gives us the SMB, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal benefits together gives us the SMB, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective The unregulated market gives us `\((P^u,Q^u)\)` as an outcome when we want `\((P^*,Q^*)\)` ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Adding the private and external marginal benefits together gives us the SMB, what we care about from the social planner or regulator's perspective The unregulated market gives us `\((P^u,Q^u)\)` as an outcome when we want `\((P^*,Q^*)\)` What's the social cost of this market failure? ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Positive externalities generate deadweight loss equal to... ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Positive externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-blue[blue] area ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Positive externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-blue[blue] area This is the difference in SMB and SMC for units where SMC < SMB: Total SMB - SMC from `\(Q^u\)` to `\(Q^*\)` ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Positive externalities generate deadweight loss equal to the .hi-blue[blue] area This is the difference in SMB and SMC for units where SMC < SMB This is the loss to society caused by the externality in the unregulated private market ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The private market produces too few vaccines The private actors are not accounting for the social benefits they are imposing on people who are not in the vaccine transaction (e.g. third parties whose health is being affected) ] --- # COVID and positive externalities <div class="vembedr" align="center"> <div> <iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/17lldWWxYC0" width="533" height="300" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="" data-external="1"></iframe> </div> </div> --- # COVID and positive externalities <div class="vembedr" align="center"> <div> <iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/4vcdJ2Zsc8U" width="533" height="300" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="" data-external="1"></iframe> </div> </div> --- # Why do externalities arise? Typically one of two reasons: -- 1. Poorly defined property rights - Who owns the right to the air? -- 2. High transactions costs - Hard to bargain over desired air quality with millions of people Lets conceptualize a model of efficient bargaining using an Edgeworth Box --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box - Two individuals: A and B - Two private goods: X and Y Each individual begins with an initial endowment of each good: - `\(A: w_X^A, w_Y^A\)` - `\(B: w_X^B, w_Y^B\)` This gives us a total endowment: - `\(W_X = w_X^A + w_X^B\)` - `\(W_Y = w_Y^A + w_Y^B\)` --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth1.png" width="80%" /> </center> --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth1.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Total vertical distance is `\(W_Y\)` Total horizontal distance is `\(W_X\)` Initial endowment is given by the empty circle Initial indifference curves for A and B are `\(UA(0)\)` and `\(UB(0)\)` ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth1.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Is there a possible Pareto improvement? e.g. can we make both A and B better off? ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth1.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Yes! ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth1.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Yes! If we move anywhere in the lens of their initial indifference curves we have a Pareto improvement If we move to an allocation where their indifference curves are .hi[tangent] to one another (e.g. the filled-in point), we have a Pareto optimum ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box In a properly functioning market: - The endowment point is well-established -- - A and B can trade X and Y to some Pareto improving point -- - They continue trading until they achieve a Pareto optimal allocation -- - This allocation lies on the .hi[contract curve]: the line consisting of all Pareto efficient allocations --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth2.png" width="50%" /> </center> --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box Now suppose Y is not a private good, but a public good/bad, e.g. smoke -- This means that A and B consume the .hi[exact same level of Y] -- Unlike our regular Edgeworth Box, now Y increases for .hi[both] A and B as we move to the top of the slide (before Y increased for B as we moved to the bottom) -- Suppose that A likes Y, but B does not -- Suppose both start off with the same quantity of X --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Depending on who has property rights, we either start at: - W1 (B has property rights) - W2 (A has property rights) Think about why these are where we must start ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W1, what happens? ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W1, what happens? A wants to have more Y, but this imposes a cost on B ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W1, what happens? A wants to have more Y, but this imposes a cost on B Therefore, A has to .hi[pay] B to get more Y ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W1, what happens? A wants to have more Y, but this imposes a cost on B Therefore, A has to .hi[pay] B to get more Y A pays B in units of X, move to Z1, Pareto optimum ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W2, what happens? ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W2, what happens? B wants to have less Y, but this imposes a cost on A ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W2, what happens? B wants to have less Y, but this imposes a cost on A Therefore, B has to .hi[pay] A to get less Y ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box .pull-left[ <center> <img src="files/02-edgeworth3.png" width="100%" /> </center> ] .pull-right[ Suppose we start at W2, what happens? B wants to have less Y, but this imposes a cost on A Therefore, B has to .hi[pay] A to get less Y B pays A in units of X, move to Z2, Pareto optimum ] --- # Why do externalities arise? Edgeworth Box In the previous example we were able to achieve the Pareto optimum even with a public good / externality -- Why? -- 1. Property rights were assigned to either A or B -- 2. Transactions costs were low (didn't have to pay a fee to trade X) --- # Property rights and externalities A solution to many externalities is to just assign property rights and let the market do its thing -- We'll talk about a few ways that we can assign property rights --- # Transactions costs and externalities Now suppose there were many non-smokers -- Even if they were assigned the property rights, it might be hard for them to bargain - Takes a lot of time to find something that works for everyone - Negotiating over how much X each person gets -- The costs of bargaining may exceed the benefits and we end up stuck at W2 --- # Transactions costs and externalities Road noise: drivers implicitly have property rights to noise around roads -- Even if you prefer quiet, you can't negotiate a payment with every loud car that might pass pay --- # The free-rider problem Externalities and public goods/bads often exhibit many of the same features Both are subject to the .hi[Free-Rider Problem] > A type of market failure that occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods (such as public roads or hospitals), or services of a communal nature do not pay for them[1] or under-pay e.g. - people don't pay their taxes for publicly-provided services - non-smokers will wait for others to pay in order to reduce smoke --- class: inverse, center, middle name: what_is_enviro # The provision of public goods <html><div style='float:left'></div><hr color='#EB811B' size=1px width=796px></html> --- # Public goods How do we efficiently provide public goods? We know: - Private goods: PMB = PMC `\(\leftrightarrow\)` SMB = SMC - Goods with negative externalities: PMB = SMC `\(\leftrightarrow\)` SMB = SMC - goods with positive externalities: SMB = PMC `\(\leftrightarrow\)` SMB = SMC -- Suppose we have a public good, e.g. depth of a river for public use How do we decide the socially efficient depth? --- # Public goods Optimal provision is .hi-blue[always] given by: SMB = SMC What are the SMB and SMC for a public good? -- Think about the characteristics of a public good, one of them is critical: -- .hi[Non-rival:] multiple people can use the same unit of a good (one person using the river doesn't 'use up' its depth) -- This means multiple people can derive benefits from the provision of 1 unit of the good --- # Optimal provision of public goods What does this mean? -- When we count up the SMB, we need to add up .hi-blue[everyone's] PMB: .hi[Optimality:] `\(SMB = \sum_i PMB_i = PMC\)` -- If we ignore the fact that public goods are non-rival, we get underprovision of the good -- e.g. the free market underprovides clean air, national defense, etc --- # Modeling the provision of public goods How do we model public goods? -- First: how do we aggregate marginal benefit or demand curves? Here's how to think about it: -- .hi-blue[For private goods:] -- Private goods are rival, only one person can consume each unit -- At each price, what is the total quantity that is demanded? -- At each price, we need to add up quantities -- Private goods: we add demand curves horizontally --- # Modeling the provision of public goods .hi-blue[For public goods:] -- Public goods are non-rival, multiple people can consume each unit -- At each quantity, what is the total marginal benefit? -- At each quantity, we need to add up PMBs/prices -- Public goods: we add demand curves vertically --- # Public goods: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ 3 different groups: boaters (B), anglers (A), and hikers (H) Each has a different marginal benefit for water depth: - Boaters: MB = 12-Q - Anglers: MB = 10-Q - Hikers: MB = 6-Q - MC of provision: MC = Q ] --- # Public goods: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Now we need to aggregate them to get the .hi[social marginal benefit] We do so by adding up the demand curves vertically: At each Q, sum the MBs ] --- # Public goods: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ Why is the aggregate demand curve kinked? Because at each quantity/depth, only certain groups are willing to use the river Kinks are at the dotted lines, where PMBs hit zero ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ At quantities > 10, only boaters are willing to pay At quantities > 6 and <= 10, only boaters and anglers are willing to pay At quantities =< 6 all groups are willing to pay to use the river ] --- # Positive externalities: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The SMB curve is: 28 - 3Q for Q <= 6 22 - 2Q for 6 < Q <= 10 12 - Q for 10 < Q <= 12 Summing the PMBs over the relevant range of Q ] --- # Public goods: graphical .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ The optimal provision of the public good is where the MC curve crosses the SMB curve This is across the middle segment Q = 22 - 2Q `\(\Rightarrow\)` Q = 22/3 The optimal quantity of Q = 22/3 is greater than the quantity any individual group would be willing to purchase ] --- # Public goods financing The socially optimal quantity is greater than the individual privately optimal quantities -- This means that the MC of provision, MC = 22/3 -- Is this the price the groups pay? -- .hi[No!] It is greater than any individual group is willing to pay -- If the government is able to provide the good, how does it finance the cost raising the river depth above zero? --- # Public goods financing It charges each group a share of this price -- What share is everyone charged? -- .hi[Lindahl pricing:] charge each group equal to their marginal benefit -- Boaters pay: 14/3 Anglers pay: 8/3 Hikers: free -- Notice that the prices sum to the marginal cost! -- Since the good is non-rival, this is enough to finance the cost --- # Public goods financing What is a key problem with Lindahl pricing? -- People can lie about which group they're in -- Anglers might say they're hikers -- It requires perfect information on behalf of the regulator