Week 6

Computational Sociology

Christopher Barrie

Introduction

- Housekeeping

- Polarization and Radicalization

Introduction: Polarization among voters

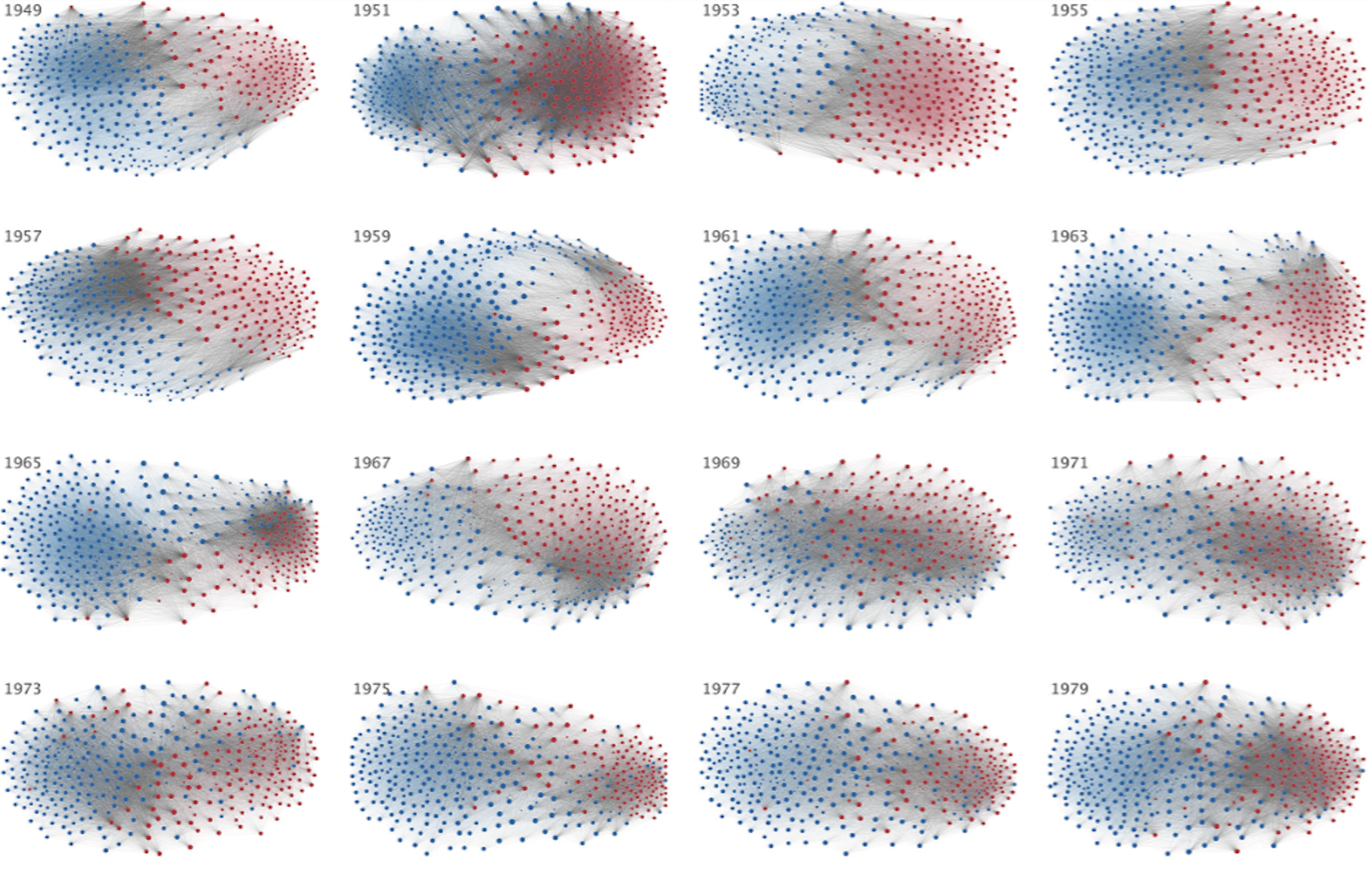

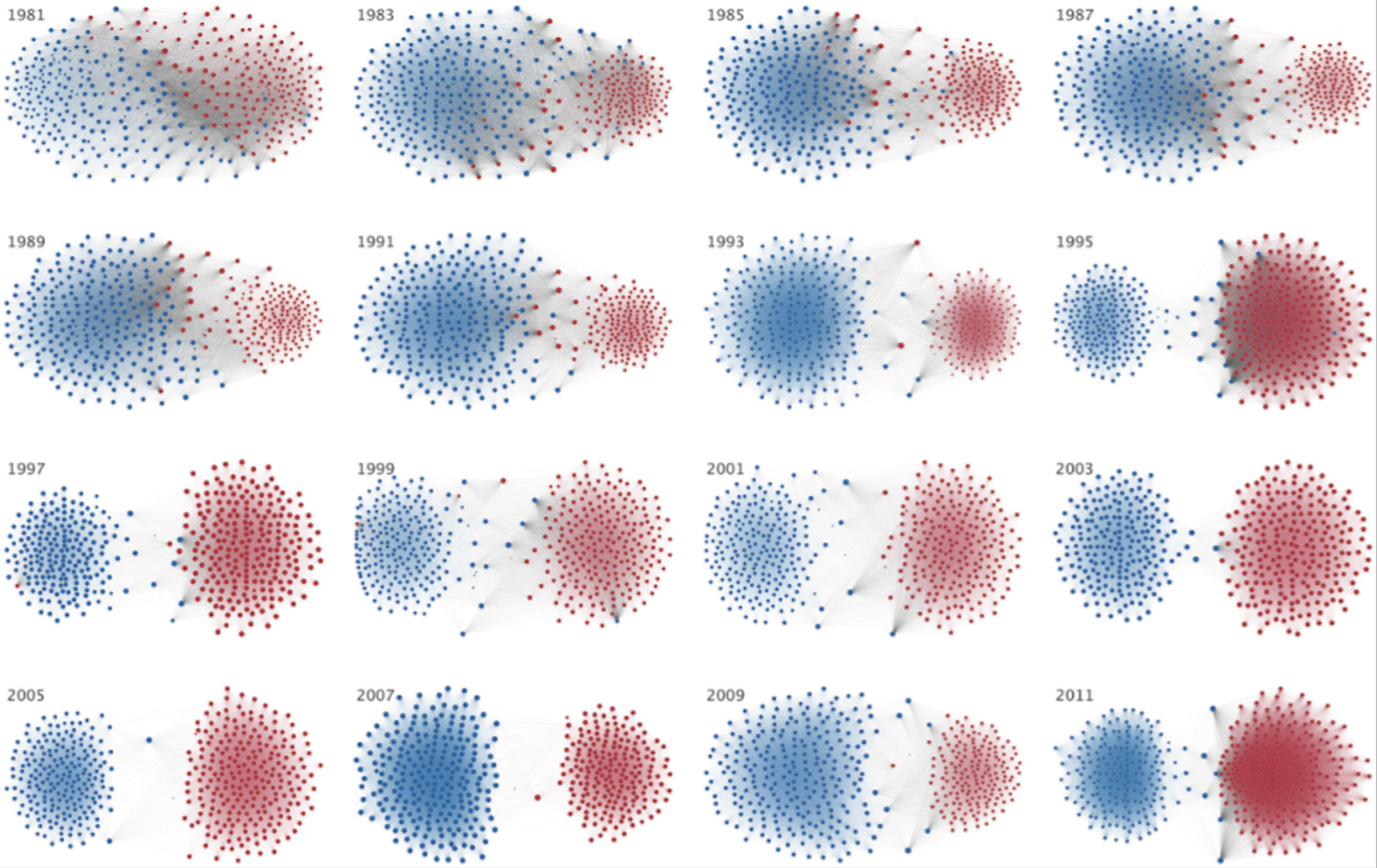

Introduction: Polarization among legislators

Introduction: Polarization among legislators

And you’ll never guess what’s to blame…

But why?

Why would platforms be polarizing?

Echo chambers/filter bubbles?

Moral outrage?

Exposure to out-groups?

Echo chambers and filter bubbles

- Impedes deliberation

- Impedes common understanding of out-group opinion

…through reinforcing mechanisms of confirmation bias and information enclaves (think back to Week 2)

Moral outrage

Humans predisposed to engaging with outrage?

Evolutionary anthropology shows it helps enforce boundaries

Online platforms biased toward outrage?

Reinforcement through engagement leads to amplification of outrage

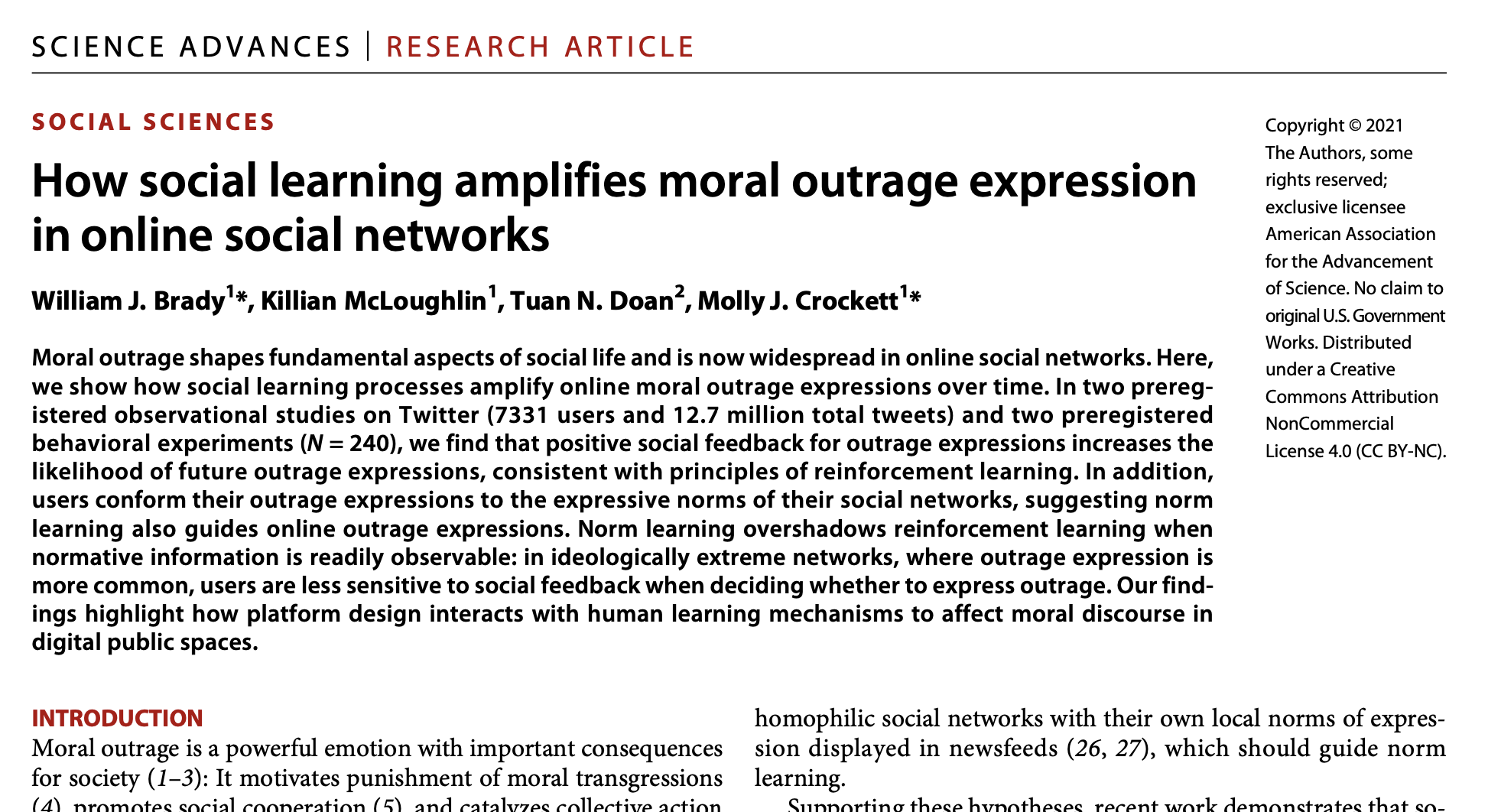

Moral outrage Brady et al. (2021)

Moral outrage

MAD Model by Brady, Crockett, and Van Bavel (2020)

Motivations: “group-identity-based motivations to share moral-emotional content;”

Attention: “that such content is especially likely to capture our attention;”

Design: “the design of social-media platforms amplifies our natural motivational and cognitive tendencies to spread such content”

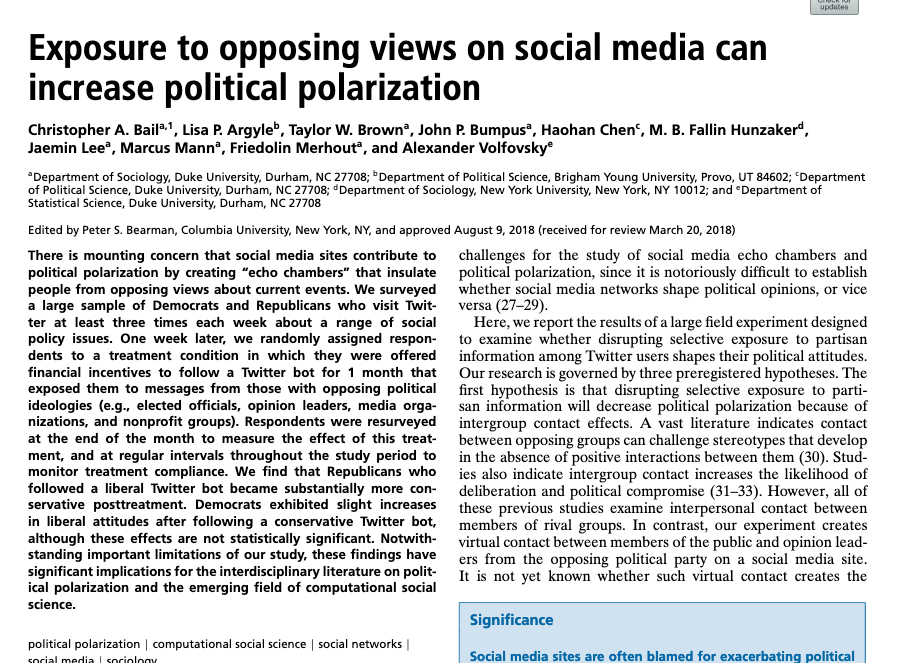

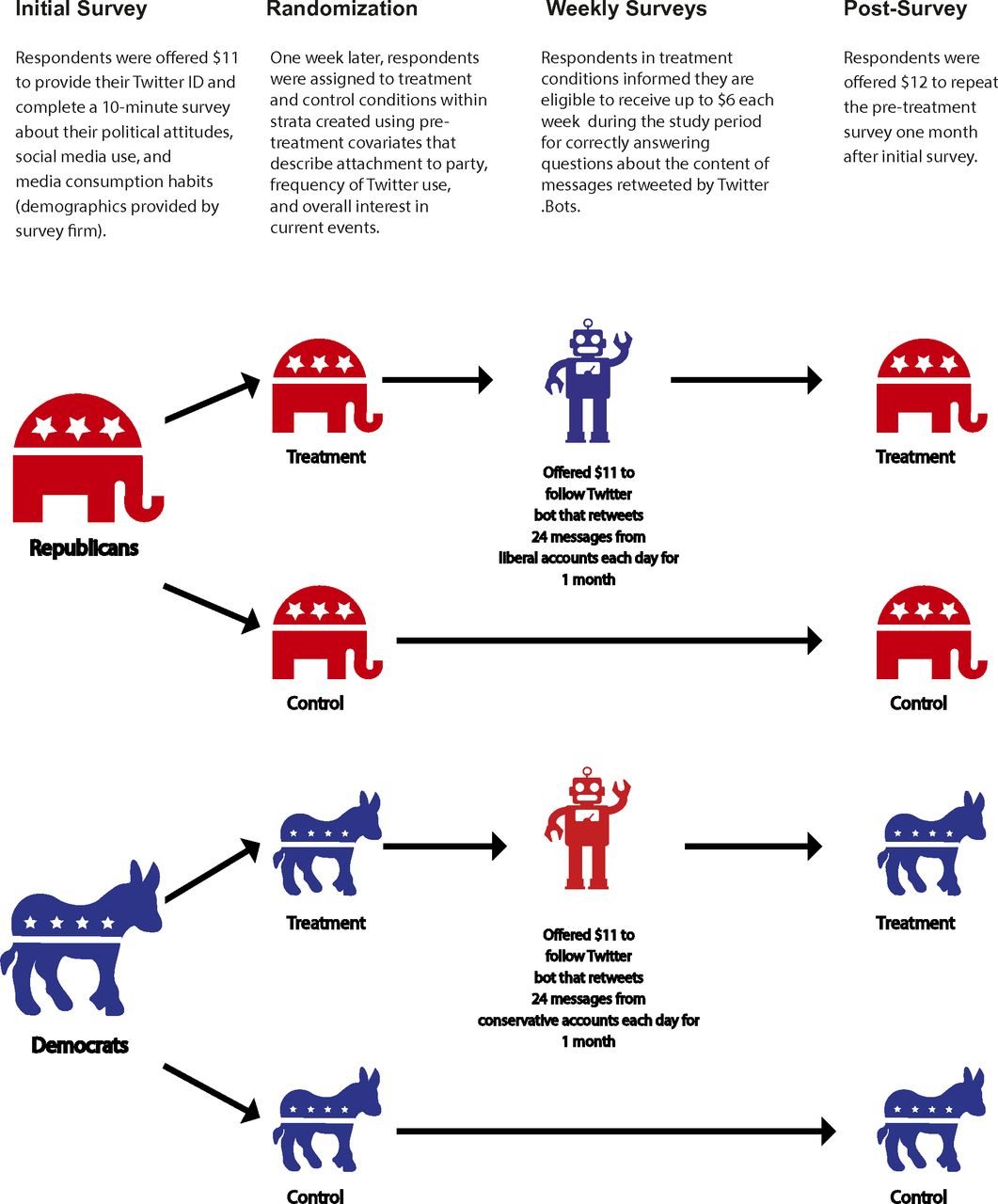

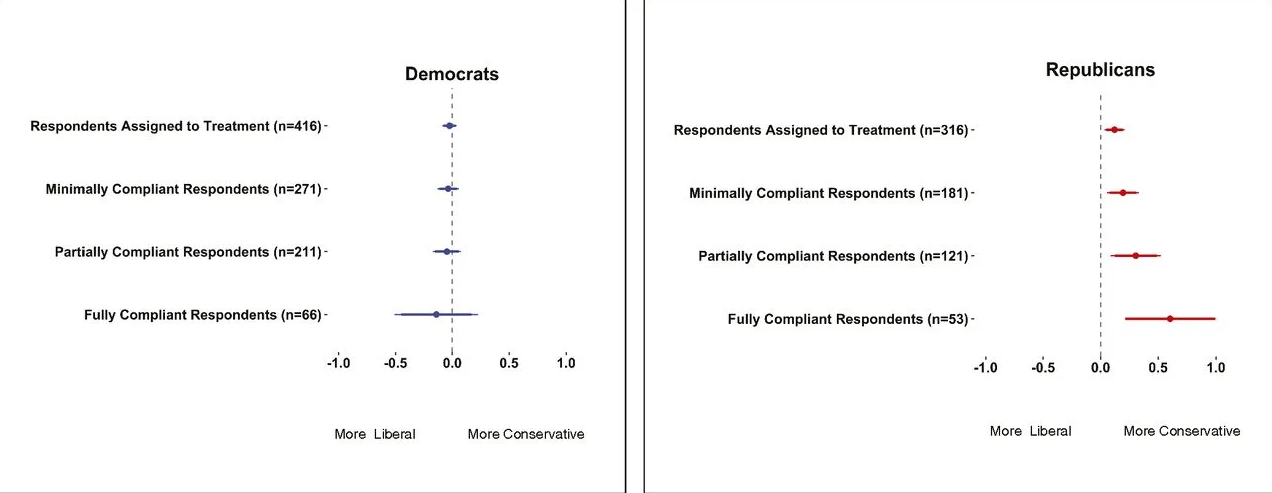

Exposure to out-groups Bail et al. (2018)

Exposure to out-groups

Backfire effects result from:

Exposure to out-groups

Exposure to out-groups

But can these all be right?

Consider echo chambers and out-group exposure theories…

So what questions should we be asking?

Some questions

- Does Internet age mean we are exposed to more or less viewpoint diversity?

- What type of incongruent information can convince?

…and back to the algorithm: Radicalization

Radicalization

So why would this make sense?

We are attracted toward the lurid, shocking, scandalous

We select into this content –>

Algorithm feeds us more back

In a reinforcing cycle

Radicalization

But these kinds of arguments have been made before too…

Think back to high-choice media environments…

Radicalization

There can be both supply-side effects (YouTube algorithm; Cable TV choice etc.)

And also demand-side effects (people select into content they were predisposed to like)

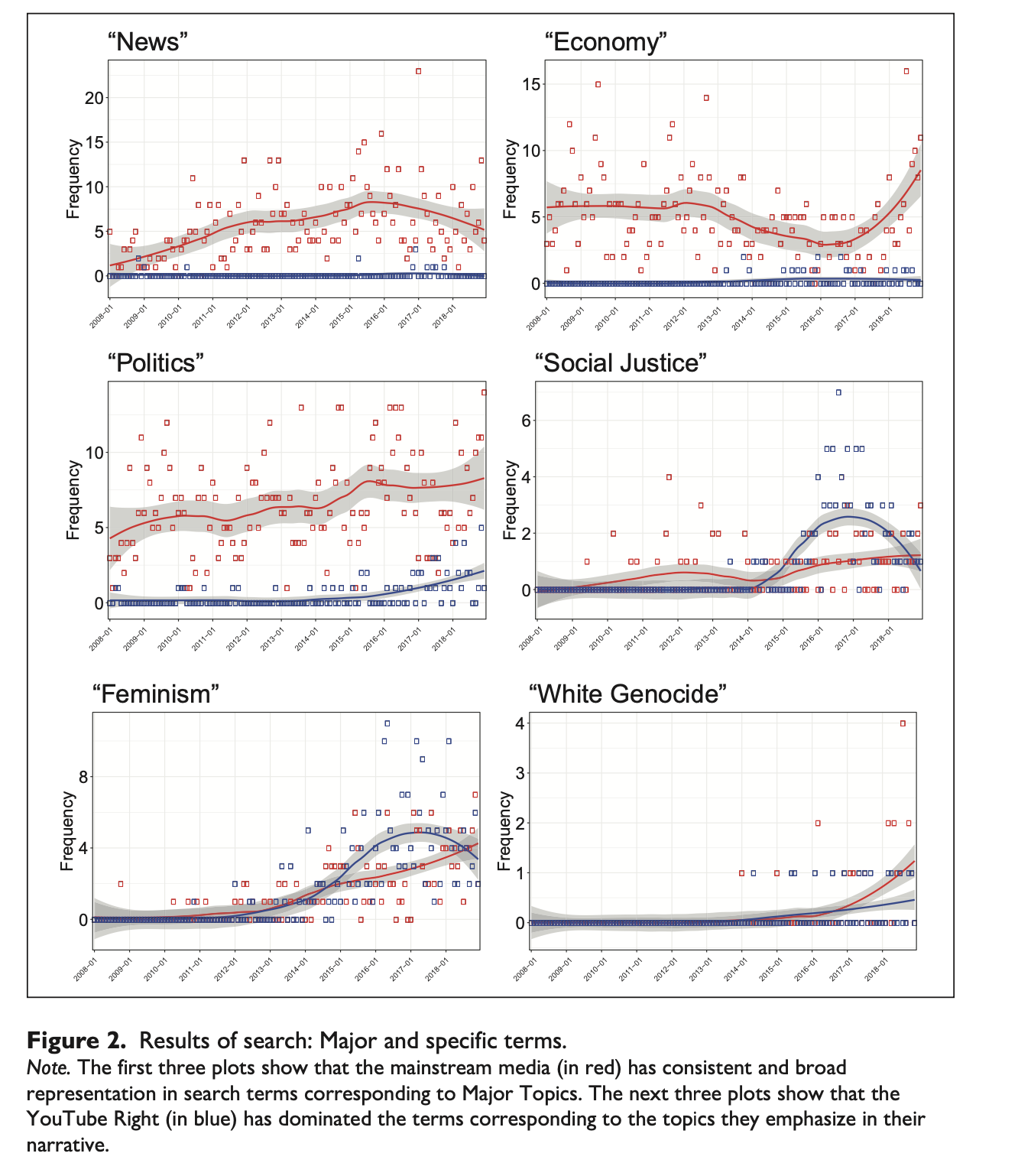

Radicalization Munger and Phillips (2020)

Radicalization

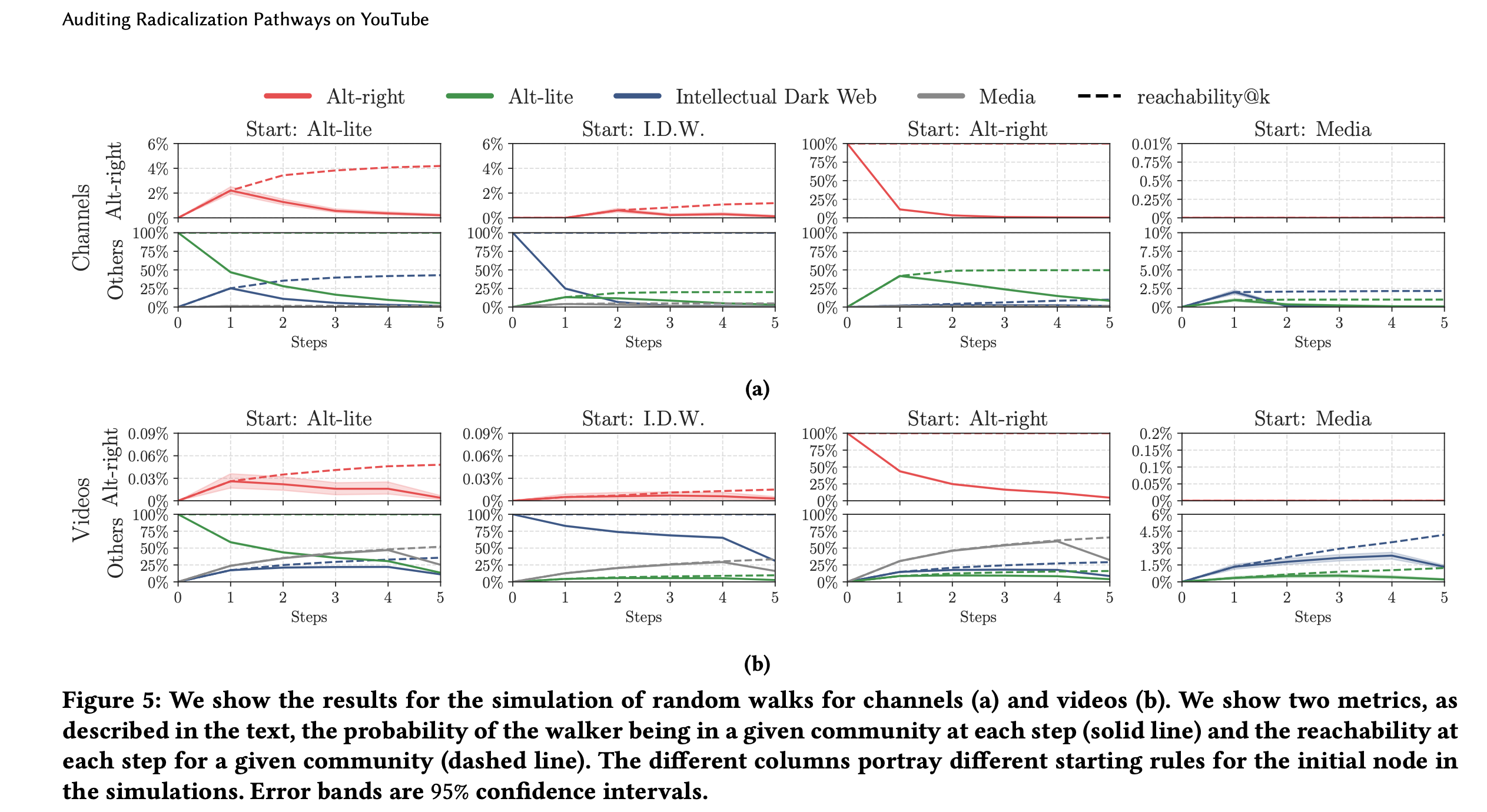

Radicalization Ribeiro et al. (2020)

Radicalization

Polarization and Radicalization

Is it as bad as they say it is?

Maybe; maybe not.

- But there has been notable lack of systematic evidence for some headline-grabbing claims

Polarization and Radicalization

What can we do better?

Get observational data (often proprietary) from companies themselves

Consider competing influences (especially for e.g., polarization)

Consider non-US contexts

A note on computational thinking

This week:

- Using platform features and APIs to simulate experience (approximation through computation and automation)

- Combining traditional experimental and automated digital techniques