Week 4

Computational Sociology

Christopher Barrie

Introduction

- Housekeeping

- Misinformation and fake news

Introduction: Misinformation and fake news

- When is the last time you read some misinfo. online?

Introduction: Misinformation and fake news

- Do you think others are more exposed than you?

- Why?

Introduction: Misinformation and fake news

- When is the last time you believed some misinformation/fake news online?

Introduction: Misinformation and fake news

- When is the last time you believed some misinformation/fake news online?

Do you think it affected you?

- How?

Why it matters

Why it matters

Why it matters

But what is it?

Often abused terms…

Misinformation: (un)knowingly false information

Disinformation: knowingly false information often spread to advance a particular cause or viewpoint

Fake news: knowingly false information often designed to look like real news

Some examples

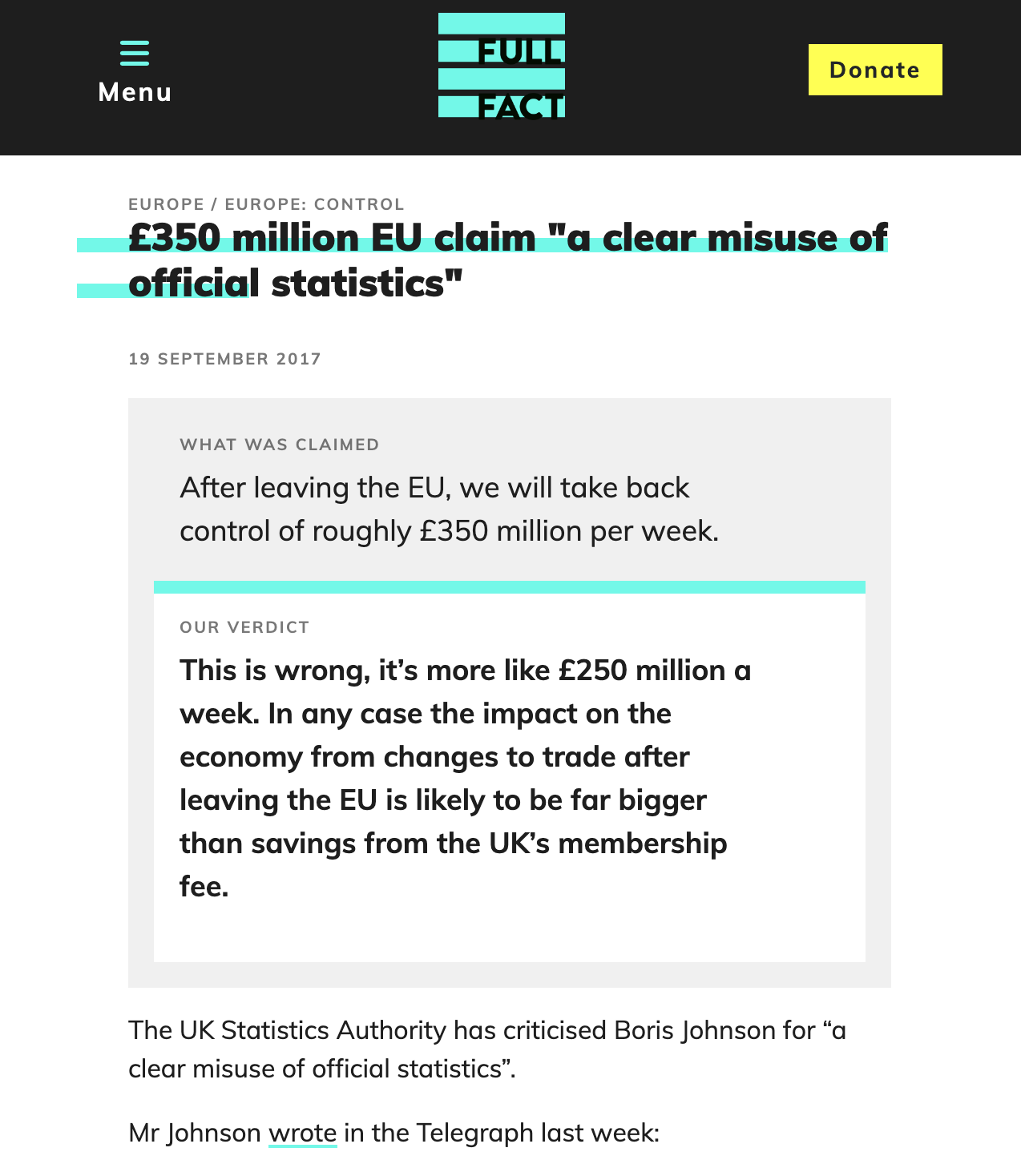

Misinformation: the claim that exiting the European Union would deliver £350m

Some examples

Disinformation: the claim that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a result of US treaty non-compliance and NATO aggression

Some examples

Fake news: the claim that Ukraine is organizing nuclear strike on Russia

So what questions should we be asking?

- Do we all get exposed to misinformation/fake news?

- What are the effects on

Individual level?

Institutional level?

So what questions should we be asking?

- Do we all get exposed to misinformation/fake news?

Exposure heterogeneity

Different types of people are more/less likely to be exposed to misinformation and fake news

Different types of people are more/less likely to believe misinformation and fake news

Exposure heterogeneity

Exposure heterogeneity

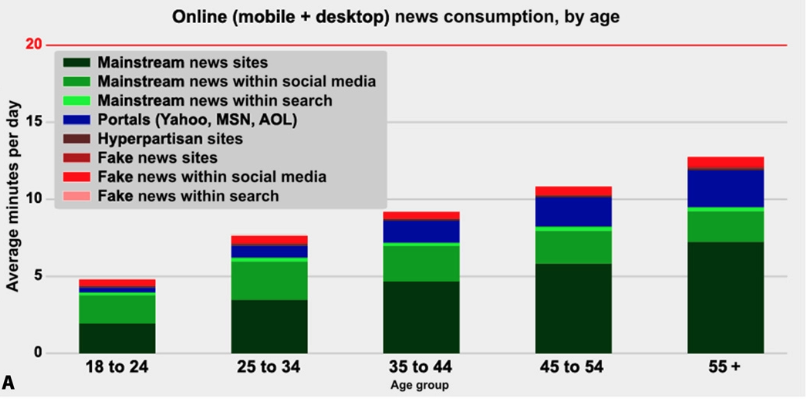

In Allen et al. (2020) we see that:

Older individuals more likely to consume fake news

2% consumed more fake news than mainstream news

- But only .7% spent more than 1 min. per day

So is 2% a big number or a small number?

What do we have to consider here?

Exposure heterogeneity

In Allen et al. (2020) we see that:

Older individuals more likely to consume fake news

2% consumed more fake news than mainstream news

- But only .7% spent more than 1 min. per day

So is 2% a big number or a small number?

What do we have to consider here?

- The (voting) population of the US

- The size of the information ecosystem

Exposure heterogeneity

Do these trends generalize?

Exposure heterogeneity

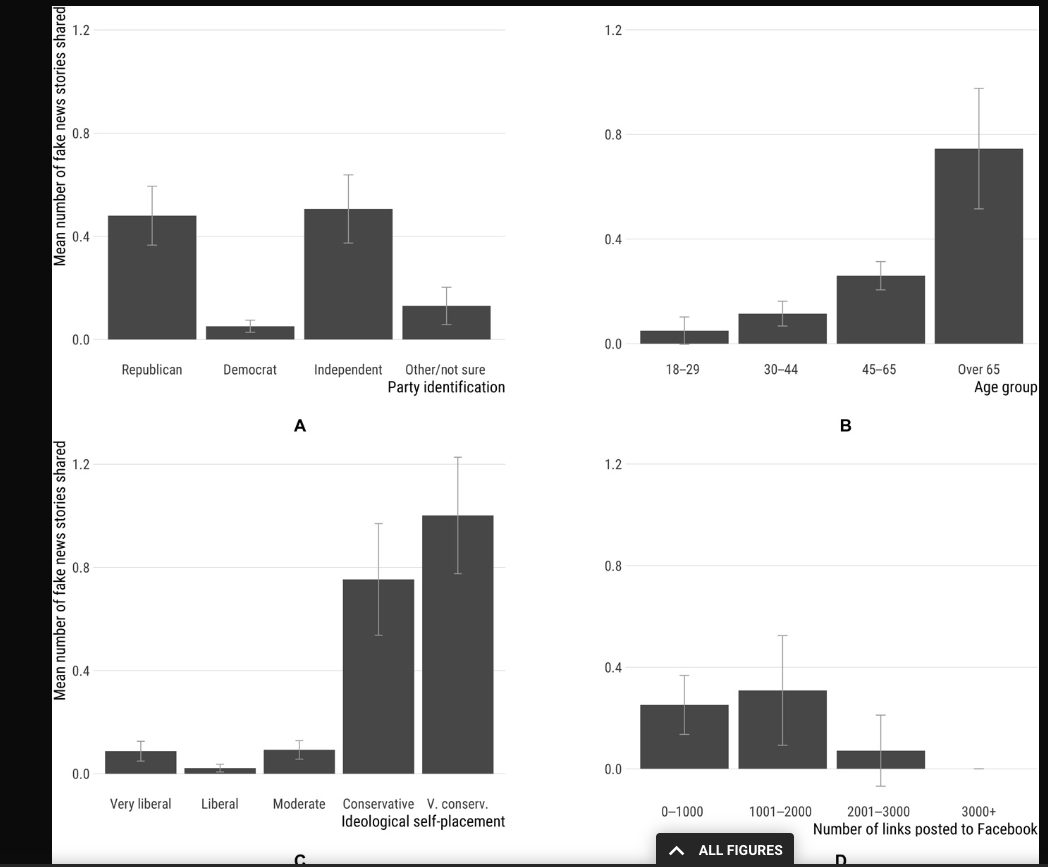

See A. Guess, Nagler, and Tucker (2019)

Exposure heterogeneity

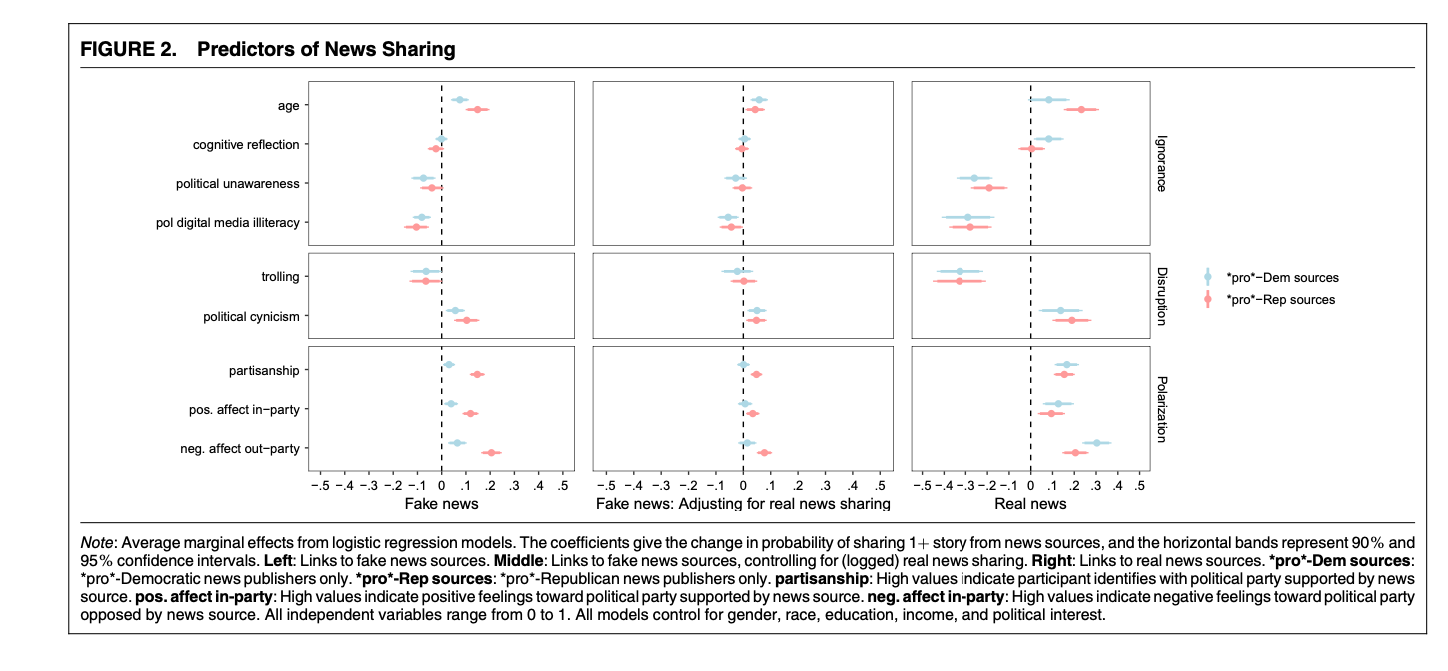

It’s not just age…

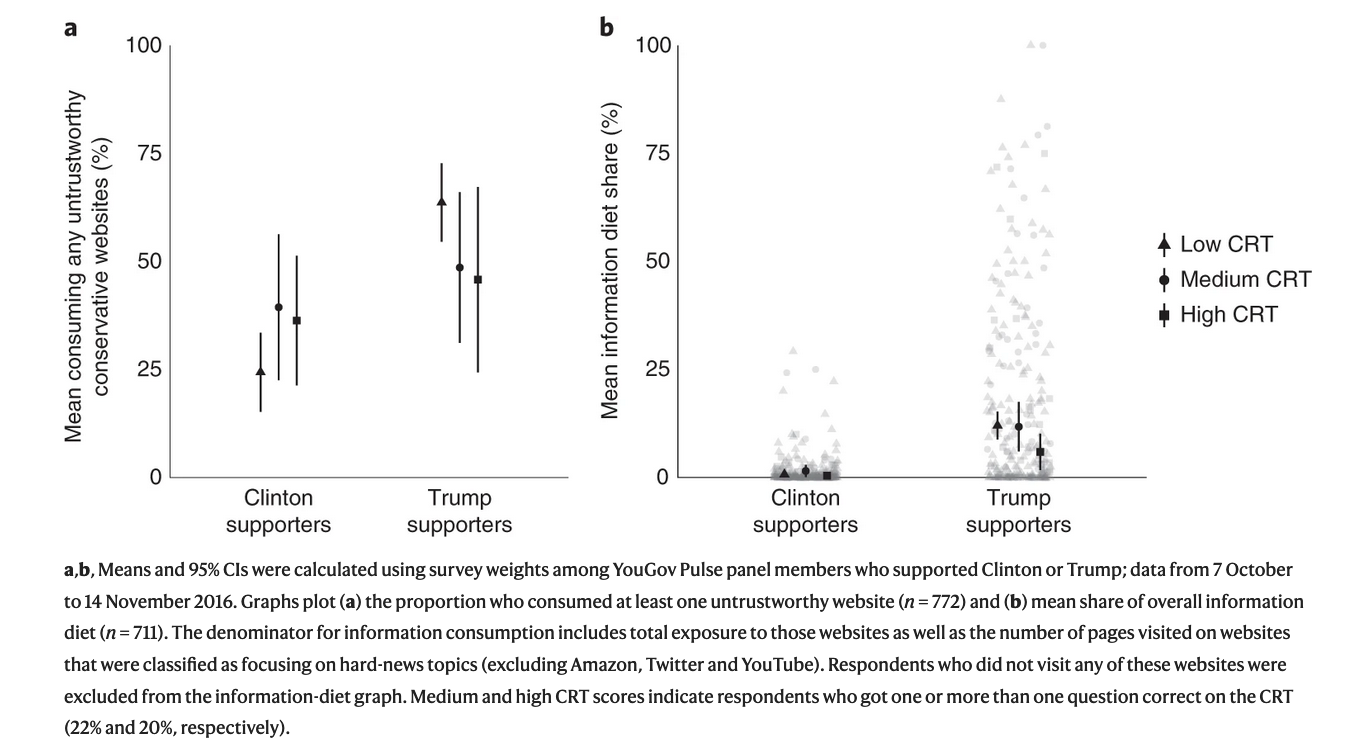

But also cognitive traits. See Pennycook and Rand (2019) for more details.

Exposure heterogeneity

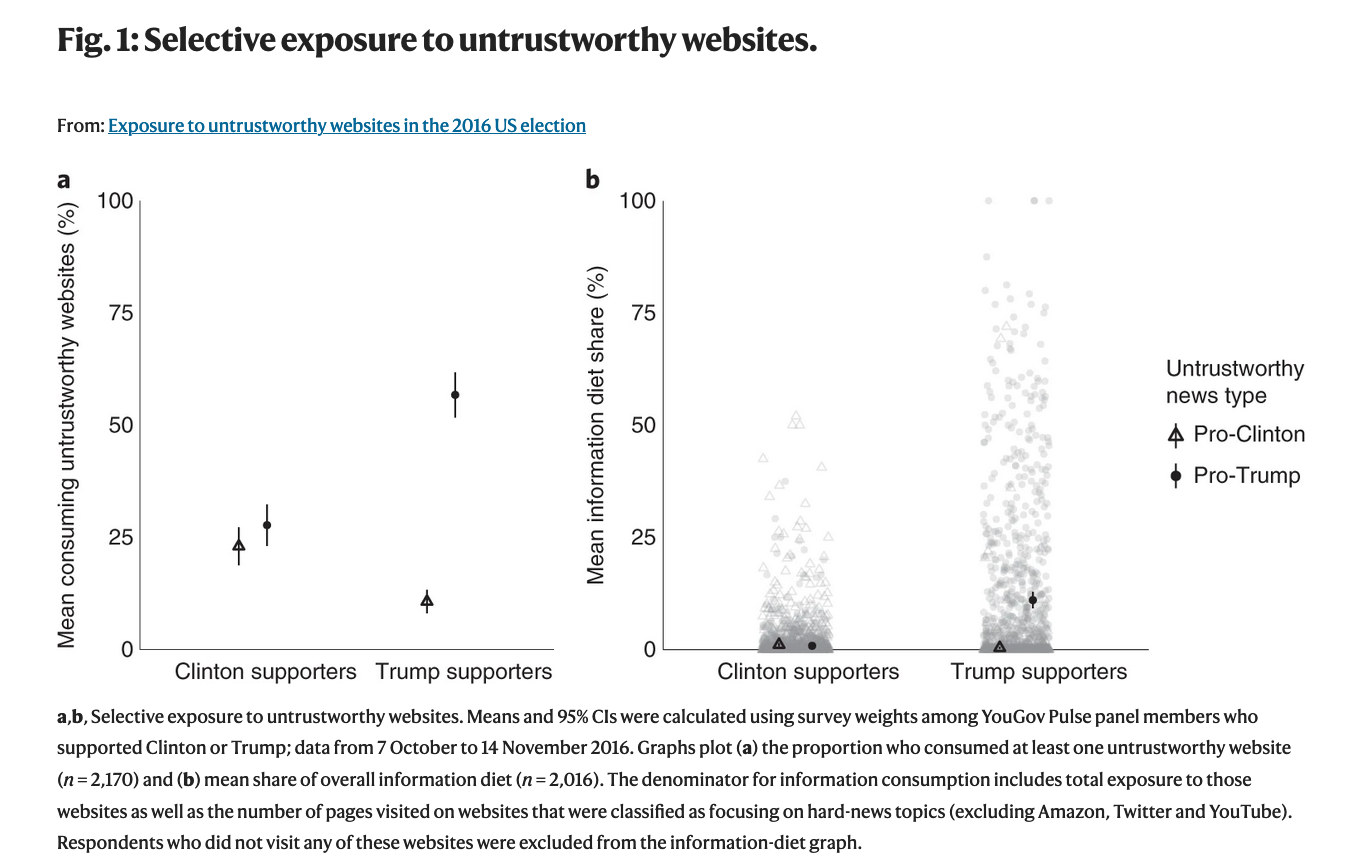

And partisan selective exposure (cf. Week 2) extends to fake news too:

Exposure heterogeneity

Confirmed by other studies too such as OSMUNDSEN et al. (2021)

A summary so far…

So consumption:

- Differs by age

- Differs by partisan position

- Differs by cognitive traits (reflection)

But what does all this do?

In other words: does consumption of fake news/misinformation have consequences for politics/society/democracy?

One hypothesis:

- Despite small overall consumption share, misinformation consumption has outsized effects among small subpopulation

But what does all this do?

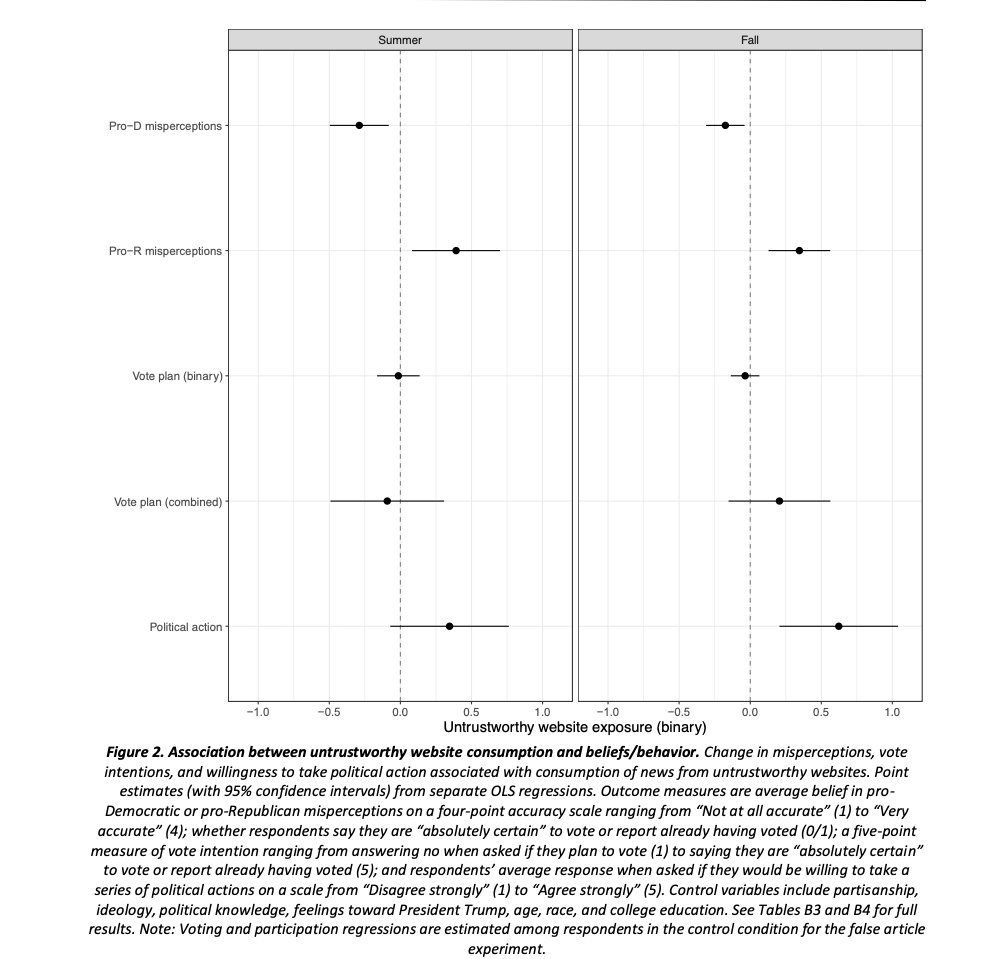

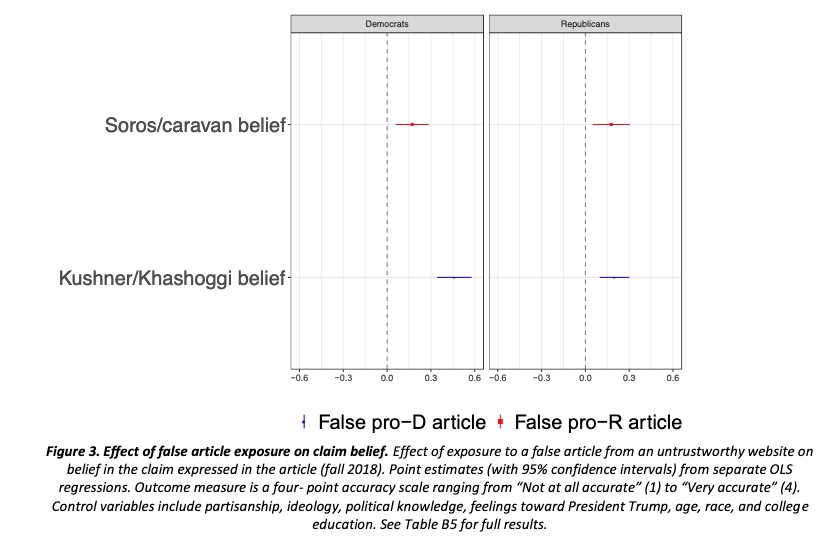

Some evidence from A. M. Guess et al. (2020)

But what does all this do?

Some evidence from A. M. Guess et al. (2020)

But what does all this do?

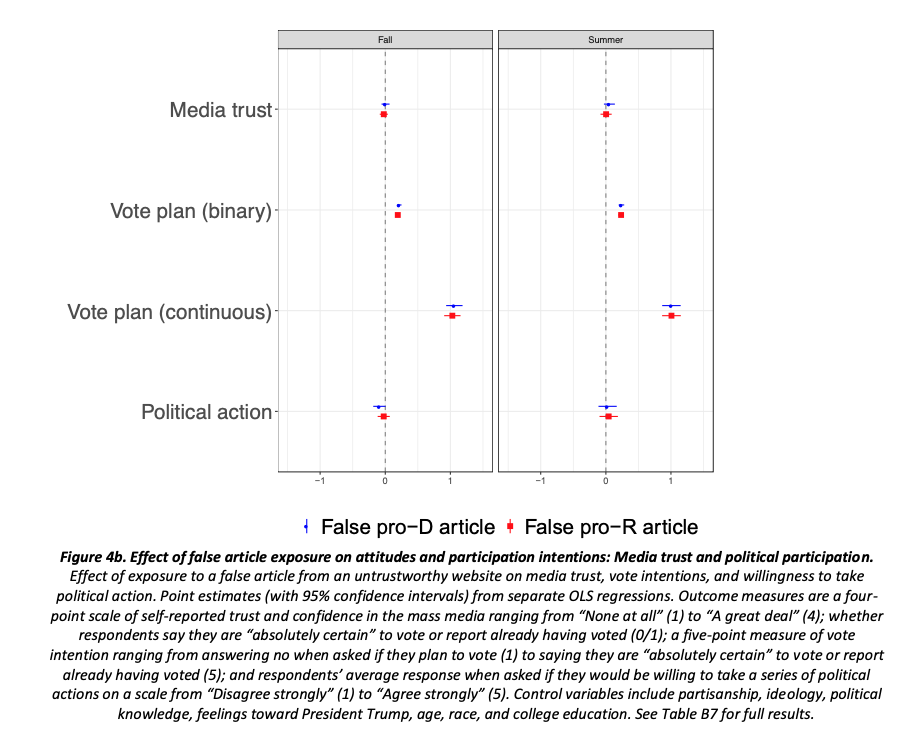

Though some experimental evidence from A. M. Guess et al. (2020) suggests effect on voting but not other types of political participation (or trust in media).

But what does all this do?

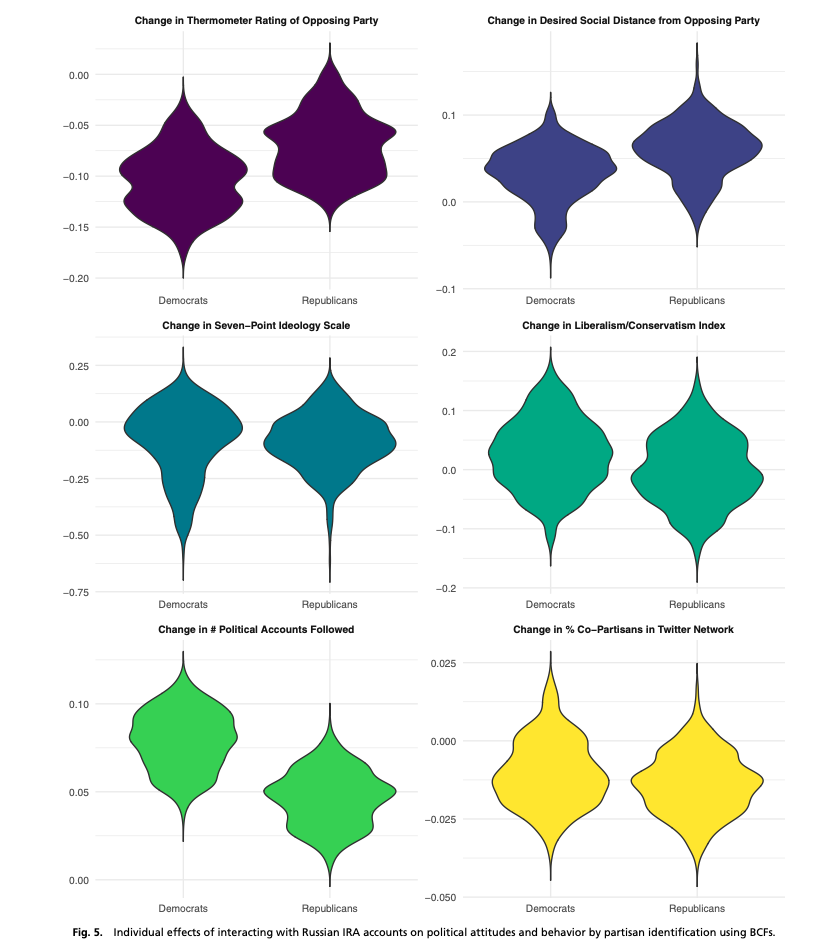

Though other work by Bail et al. (2019) shows that exposure to misinformation by Internet Research Agency trolls had no effect on important political attitudes and behaviours

In summary

- Different types of people are exposed to different types of untrustworthy content

- The size of this consumption is likely small

- But what is small after all…?

- The effects are most obvious for beliefs

- More work needed on political behavioural effects

A note on computational thinking

This week:

- We see what’s measurable (and what isn’t) using digital data

- e.g., with the Allen et al. (2020) article

- We see how we can extend and validate theoretical models by using digital trace data

- e.g., with the article by Vosoughi, Roy, and Aral (2018)

- We see how we can combine multiple sources of information to approach an approximate solution to a question

- e.g. with the article by A. M. Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler (2020)