Week 3

Computational Sociology

Christopher Barrie

Introduction

- Housekeeping

- Web tracking and Networks

Introduction: Web tracking

Web tracking a core concern in the study of digital society

1994: HTTP cookie is introduced

2010: term “zombie cookies” is coined

2020: Apple bans third-party cookies

Introduction: Web tracking

And has led to major legislation, e.g.:

GDPR in EU

Draft Online Safety Bill in UK

Introduction: Web tracking

Is now core of enornmous marketplace:

- “data profiling” or “cookie profiling”

And you can view your own profile!

But it’s also useful for us…

Web-tracking methods make accessible:

Granular, real-time data on information consumption

Amenable to experimental intervention

Complementary data source for survey research

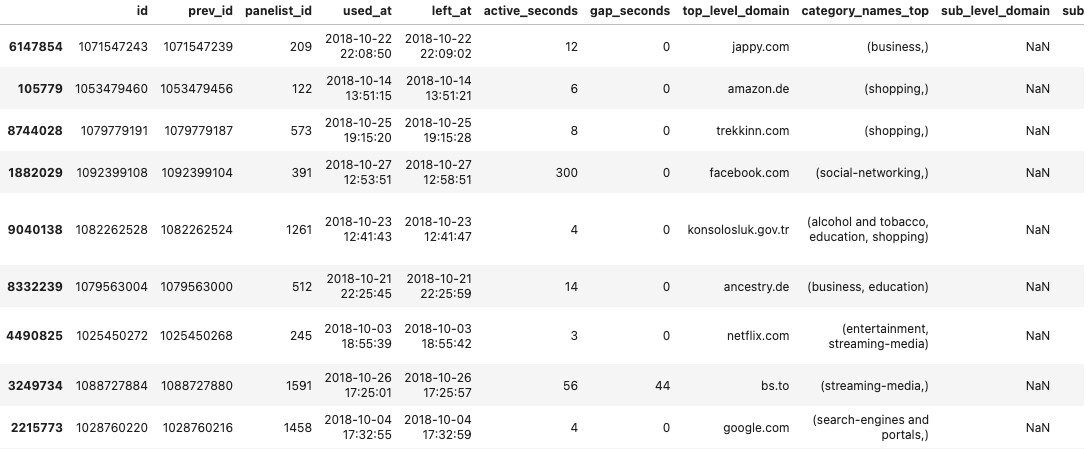

Web-tracking data

What does it look like?

Comes in many forms that might include

- Website visited

- Search terms (inputs)

- Time spent

- Website from which link originated (e.g., going to another website from Twitter)

Web-tracking data

What does it look like?

And some add-ons can measure even more, such as:

- Section of screen scrolled to

- Time spent looking at section

- Button clicks (events)

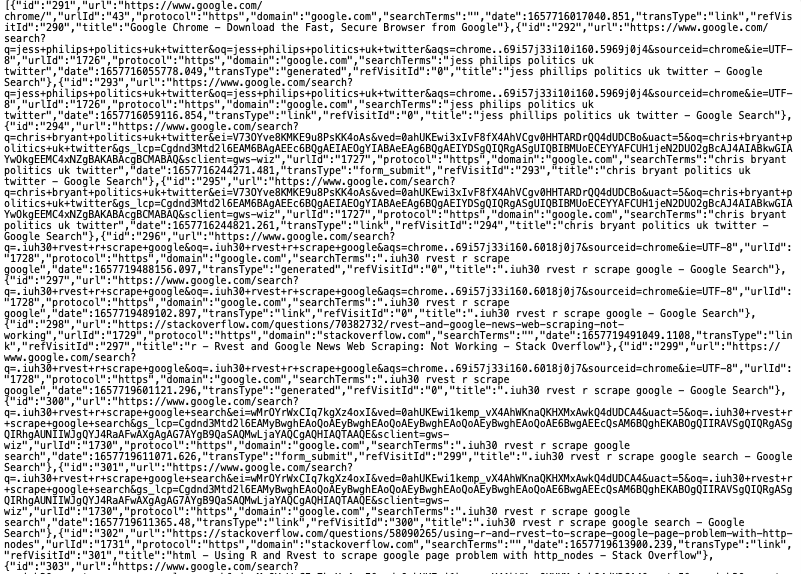

You can look at this too

There are many add-ons/extensions to popular browsers such as Chrome and Firefox.

These include:

An example from Kulshrestha et al. (2020)

An example from…me

What can we do with this data?

View and predicts user habits:

Kulshrestha et al. (2020) find very predictable patterns of routineness

estimate aggregate patterns of information consumption

What can we do with this data?

Pair with surveys to:

understand variation according to demographic attributes

understand variation according to ideological attributes

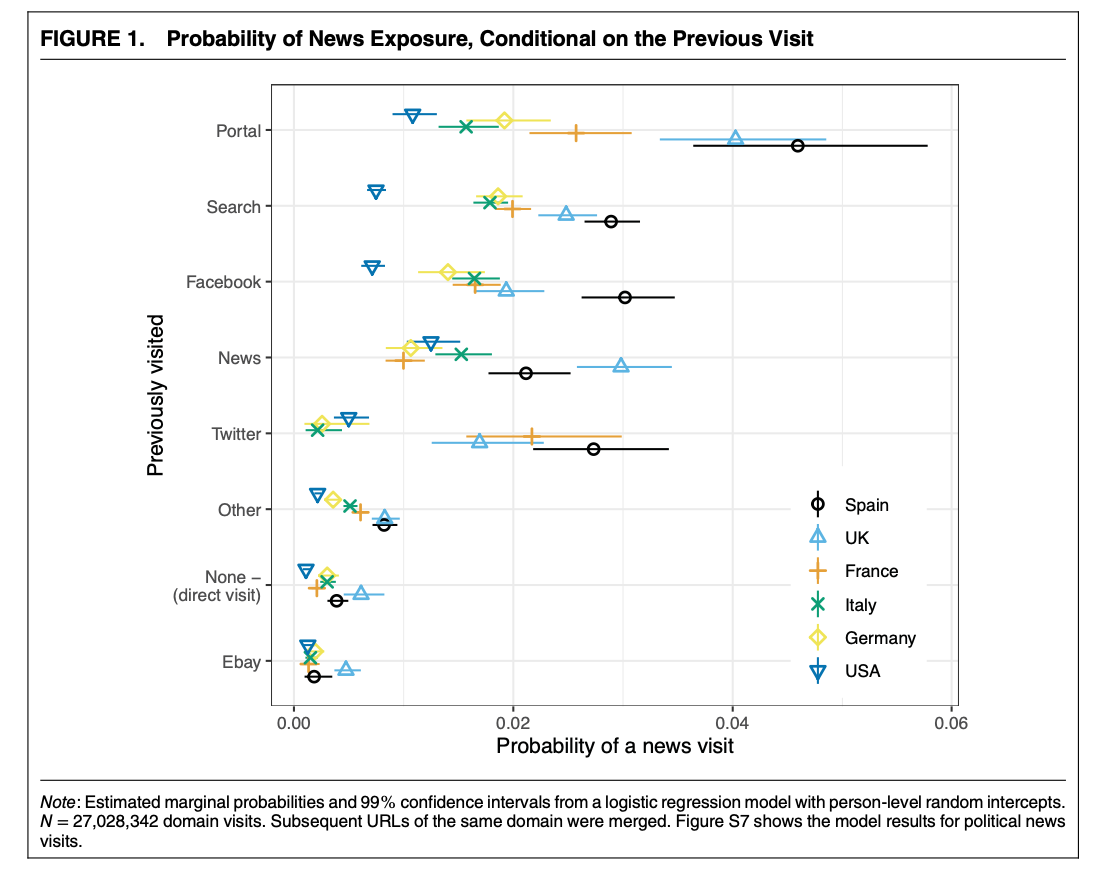

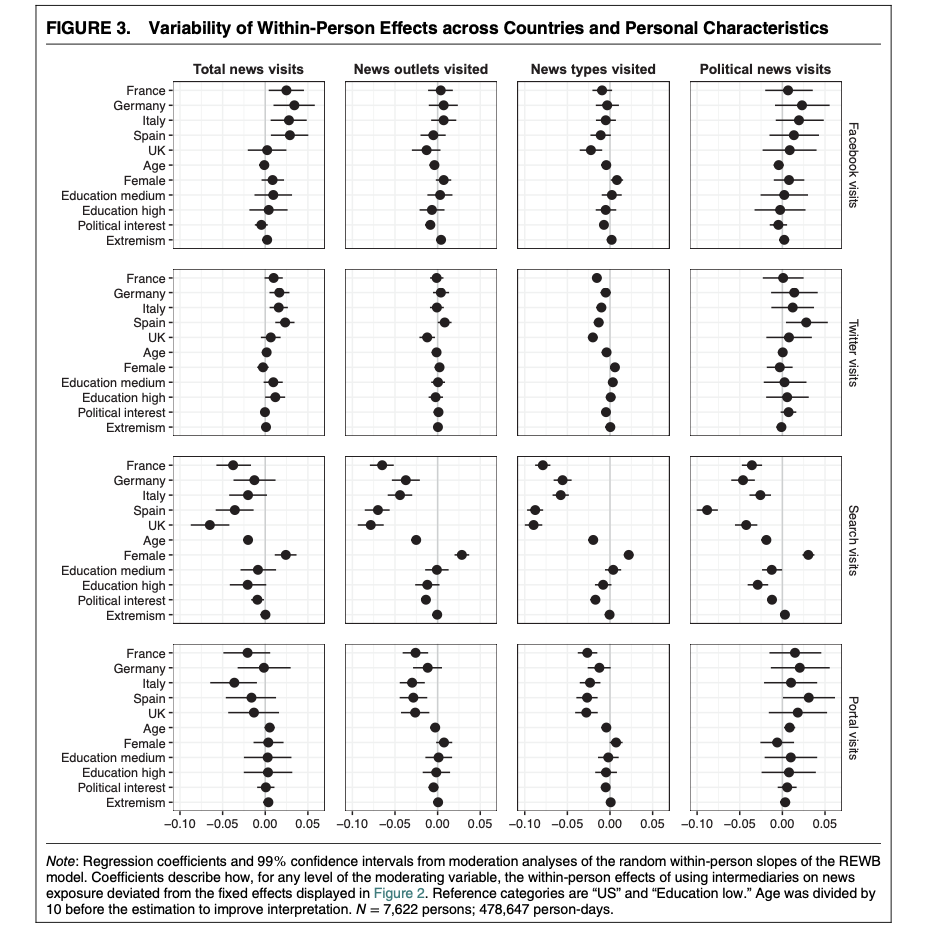

Example: STIER et al. (2021)

7,775 participants who have web-tracking software installed

surveyed for attributes often linked to information inequality

- country, age, gender, education, political interest, and political extremism

surveys + web-tracking behaviour combined

Example: STIER et al. (2021)

Example: STIER et al. (2021)

Webpages classified accorded to hand-coded list + ML classifier

Panel structure that controls for within-person characteristics

Example: STIER et al. (2021)

Introduction: Networks

What we do and see online is often organized in the form of interactions or ties, e.g.:

Emailing a friend or colleague

Retweeting a news article

Hyperlinks within domains

Introduction: Networks

Any such interaction or link therefore has two types of data associated:

- The origin of the link (e.g., the person who sent the email)

- The destination of the link (e.g., the recipient of that email)

Introduction: Networks

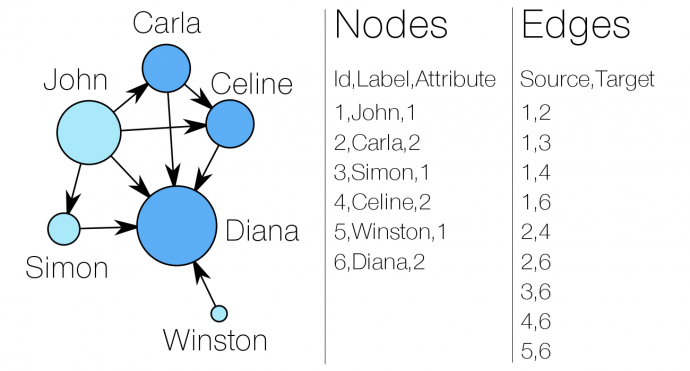

And these elements of network data have their names:

- An individual unit in the network: a “node” or “vertex” (plu.: vertices)

- A link between one node and another node: an “edge” or a “tie”

What does the data look like?

What does the data look like?

And it’s useful for us…

For estimating political preferences (cf. last week’s lecture)

For understanding information consumption and e.g.:

polarization in news exposure

diversity in news consumption

For tracking information diffusion and e.g.:

spread of rumours

spread of fake news

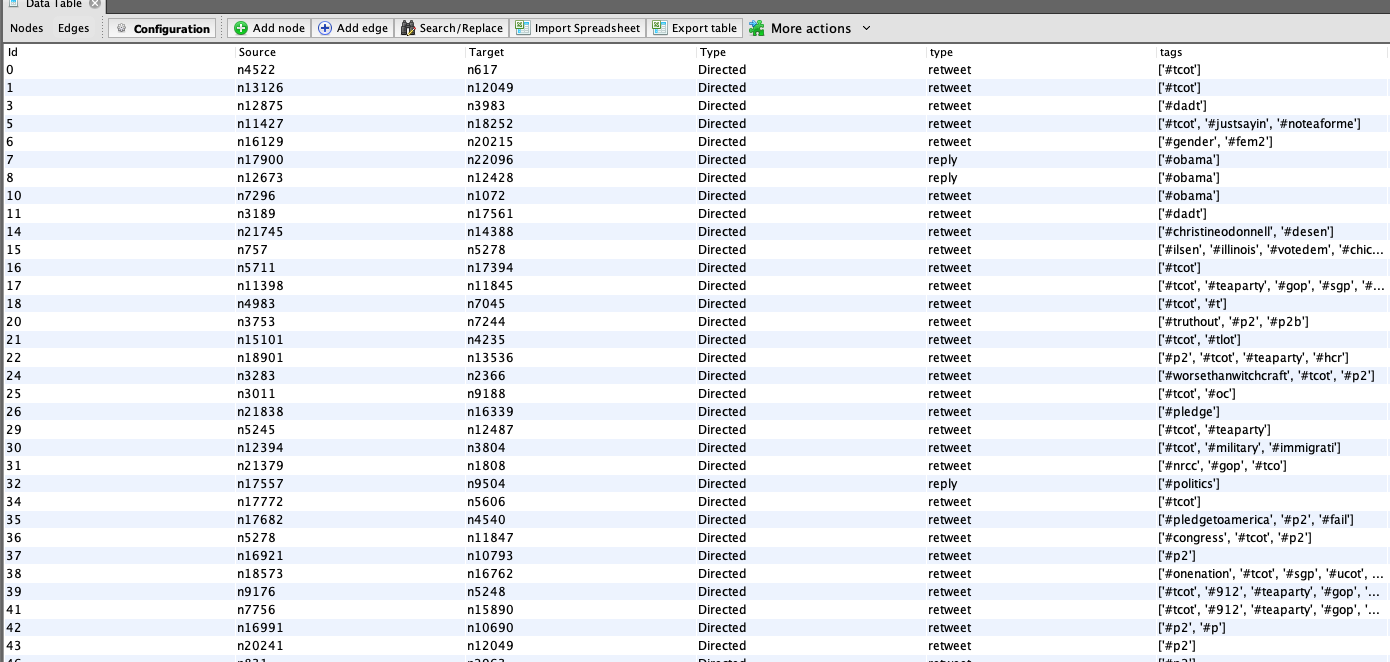

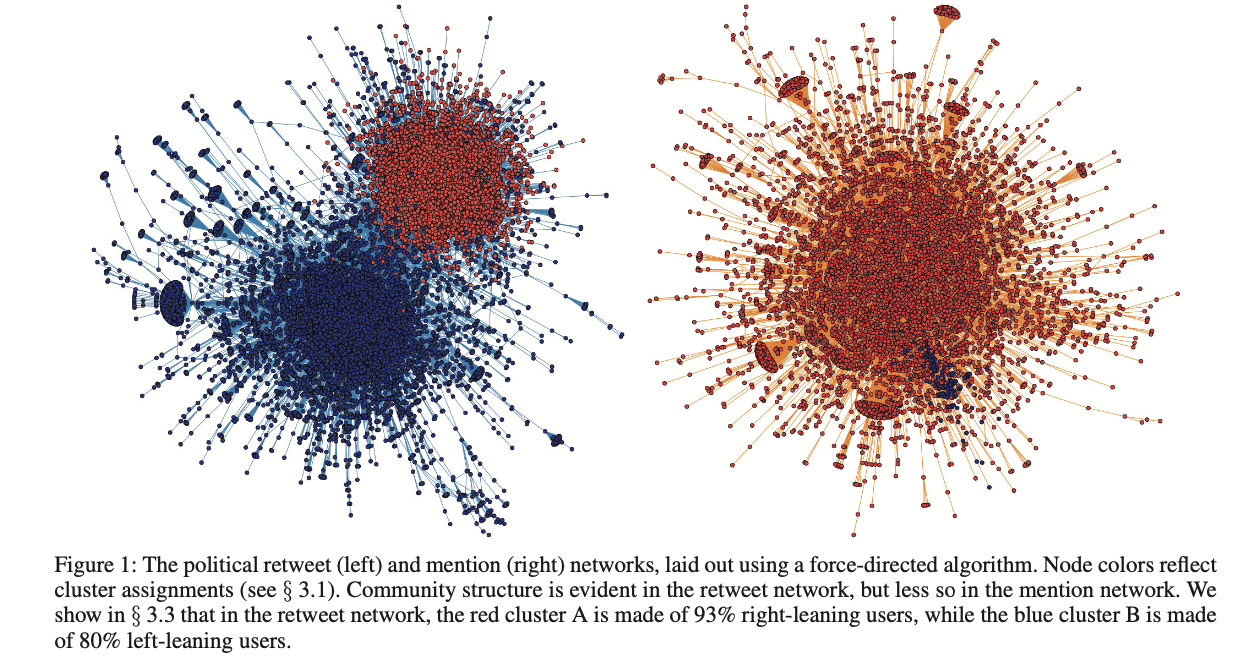

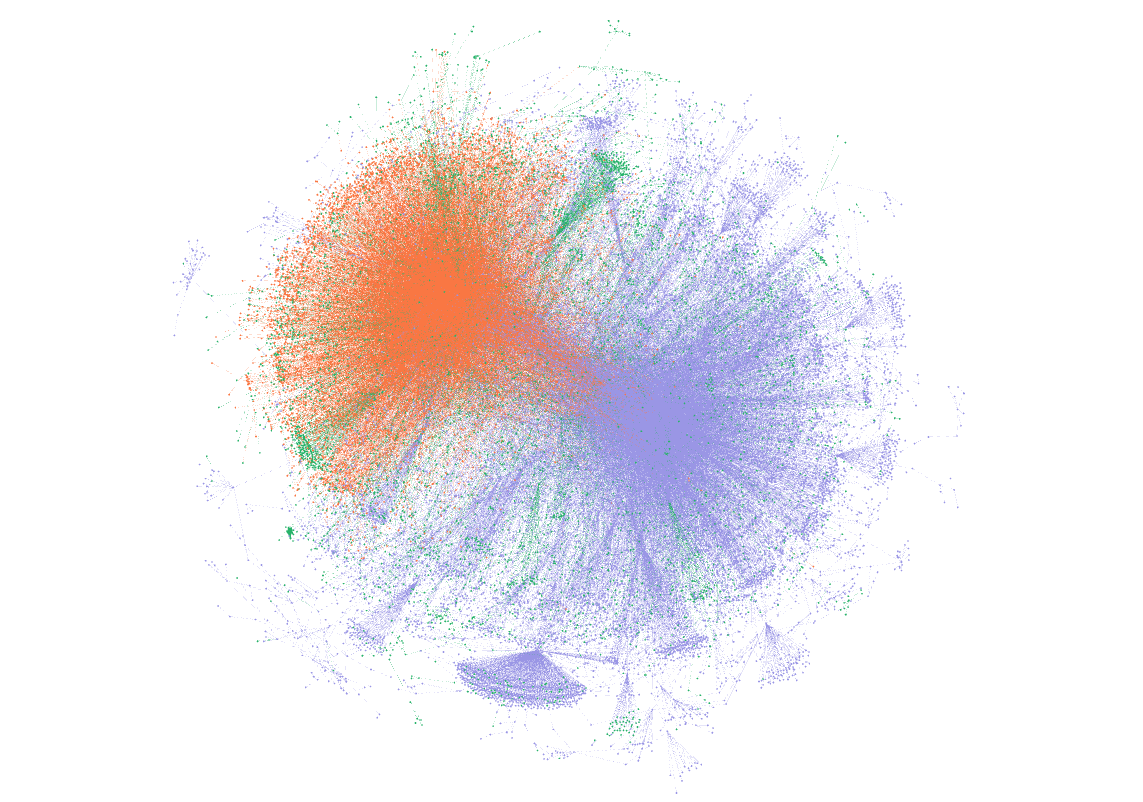

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

Data: 250,000 tweets collected before 2010 US midterms

45,000 individual users

Tweets tagged for political content

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

Tagging of political content was with

Jaccard coefficient to determine frequently co-occurring tweets:

- \(\sigma(S,T) = \frac{|S\cap T|}{|S\cup T|}\) where \(S\) is a set of tweets containing seed hashtag and \(T\) a set of tweets containing another hashtag

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

Then filtered data according to appearance of political hashtags

Generated retweet and mentions node and edge data

- Plotted data using community detection algorithm

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

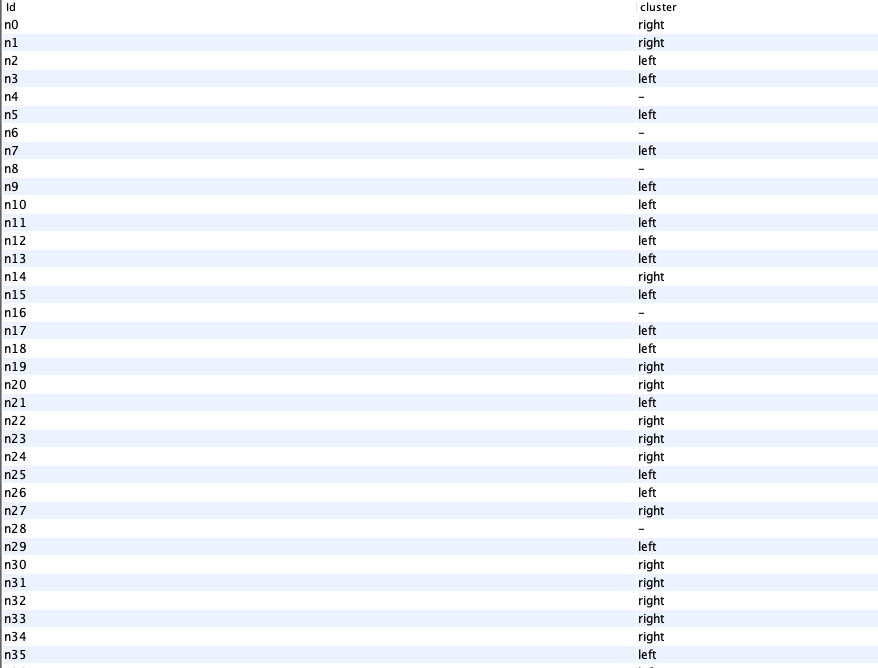

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

Example: Conover et al. (2011)

Manually annotated 1000 tweets for left-right affiliation

Measured frequency of cross-ideological retweeting/mentioning

Inferred overall community membership from these statistics

Inferred membership of (left-right) community from community detection statistic

A note on computational thinking

Taking digital trace data and:

Asking questions that can be articulated in computational terms

Enriching that data (through computational/non-computational means)

Abstracting that data into approximate solution